By: William A. Kerr

Bioresourse Policy, Business and Economics, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

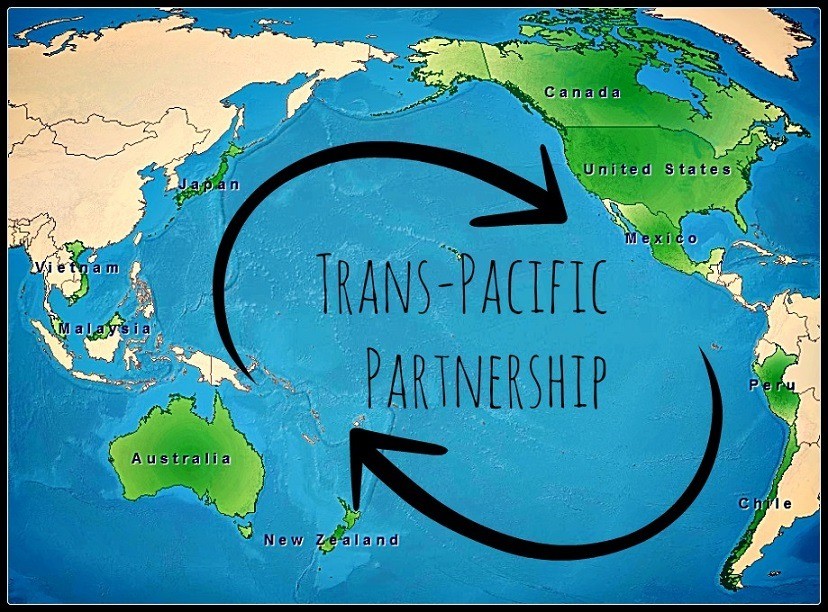

In early October, Canada and eleven other countries reached agreement on a major trade liberalization initiative, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The final agreement was accompanied by considerable theatre of negotiators threatening failure and negotiations continuing long after the announced deadline, frequently into the early morning hours. Given considerable media attention prior to the final negotiation session where both jubilation and angst were being expressed by various stakeholders and politicians, it is not surprising that members of the public would like to know what it all means. Most experts, however, are suggesting that the answer will have to wait until we see the details. The absence of detail allows anyone to usefully spin the agreement to push their own agenda and message. So the question is; why are the details so slow in coming? There are two reasons for this. The first is largely mechanical and relates to the preparation of official documents. The second relates to determining the impacts once the details are known.

In early October, Canada and eleven other countries reached agreement on a major trade liberalization initiative, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The final agreement was accompanied by considerable theatre of negotiators threatening failure and negotiations continuing long after the announced deadline, frequently into the early morning hours. Given considerable media attention prior to the final negotiation session where both jubilation and angst were being expressed by various stakeholders and politicians, it is not surprising that members of the public would like to know what it all means. Most experts, however, are suggesting that the answer will have to wait until we see the details. The absence of detail allows anyone to usefully spin the agreement to push their own agenda and message. So the question is; why are the details so slow in coming? There are two reasons for this. The first is largely mechanical and relates to the preparation of official documents. The second relates to determining the impacts once the details are known.

Trade agreements are very precise documents, they have to be. Once they are signed they cannot be changed. Subtle meanings in wording can be legally binding and legally interpreted in ways that were not the intent of the negotiators when they agreed. Thus, what is agreed in the heat of the negotiations must be turned into legal text by lawyers and reviewed by the negotiators. The TPP is reportedly 1500 pages of relatively dense text. The legal talent that is required to undertake this work is very specialized and such individuals are limited in number. The process will take time. While a government might like to release details before this process is completed, it must wait until all other governments sign-off on the text. They might inadvertently release an interpretation another government does not agree with – leading to political problems for that government at home and soured relations between the countries.

The TPP is further complicated by there being 12 countries involved having six additional official languages – Spanish, Japanese, Vietnamese, Malay, Tamil, Mandarin, and French. Given that the legislatures of the TPP countries must each consider the agreement, it must be translated into all the official languages once the English text is agreed. Official translators with legal skills are not common. Translations are very tricky and it is often difficult to find a translation that conveys the intended meaning. Further, the translations must be widely shared and reviewed as once agreed, the wording is legally binding and can’t be changed. Again, the release of details will have to await the sign-off by all governments. While governments will obviously release some relatively vague details due to public pressure, fully understanding what it means, in a legal sense, will take time. Then the 1500-odd pages will have to be read and digested by the public – all of this could take well into 2016.

Once the details are released, then the potential impact must be assessed. This is always difficult as forecasting the changes in trade will depend on how well Canadian firms respond to the new opportunities of the TPP agreement and how they adapt to the increased presence of foreign competitors as well as the ambition of the agreement itself. The benefits from trade come in the long run from moving resources out of what a country does relatively inefficiently into what we do relatively efficiently. In the short run there will always be both winners and losers. Usually, the changes for the least competitive sectors are slated to take place over 15 years , or longer, on a phase in – or there may be no liberalization in that sector. Lots of other changes will have larger short run effects: oil prices, exchange rates, technological change (fracking for example), and unstable weather. Without trade liberalization, the gains from trade can never be realized.