Throughout this series, I’ve discussed the value of fish to Canada and how our institutions ensure product safety. As a result of that research, I rudimentarily understand that aquaculture, much like other forms of agriculture, faces environmental tradeoffs. I also know, being familiar with the driving forces of resource-based industry and the pillars of sustainability, that it does not suit farmers to destroy the areas in which they work. This makes me perhaps slightly oversensitive to dissenting opinions that call into question the ethicality of farmers, as is progressing in the Discovery Islands of British Columbia. It frustrates me when disinformation based on fears or incorrect assumptions or guesses infect farm credibility. It subsequently angers me when fisheries ministers with health services and forestry backgrounds make policy decisions (and double down on them) based on impulsivity. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with trusting a gut, but I have a problem when no effort is put into confirming the validity of the feeling and associated decisions impact others’ livelihoods. There are, of course, tradeoffs to fish farms, much like how there are tradeoffs to sustainability policies and possible solutions. However, government has spent time removing itself from community-level aquaculture such that their understanding is incomplete, and makes their sudden farm closure declarations so baffling.

Who Cares?

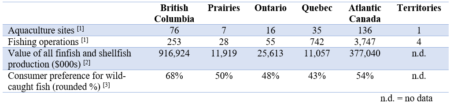

While food companies may prey upon a general lack of fish farm understanding and the genuine (but easily overinflated) consumer concerns over animal welfare by promoting the “superior quality” of wild-caught options, fish farms are vital to ocean sustainability and economic prowess. Over time, maintaining farm quality, leading to gaps in monitoring and outdated government understanding on which policies are based. As a result, activism and propaganda have taken over the conversation – and continue to do so – swaying decision-makers into making potentially detrimental decisions for the industry. While some opinions towards aquaculture and ocean-based salmon farming, in particular, can be influenced by exposure (Table 1), that exposure really represents an increased ease of knowledge accessibility. However, as we see on both Canadian coasts, increased exposure to aquaculture has signalled a slight negative opinion of farmed options, and the apathy to wild-caught elsewhere likely reflective of available seafood sources in the interior.

The human consumption market is promoted with health sentiments, as cited by nearly two-thirds of Canadians as the reason for choosing seafood and echoed by Health Canada’s calls for increased seafood (lean protein) consumption. Canadian concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic led to slight (localized) consumption increases of select seafood products, albeit inconsistently and only those products that cost less than other protein alternatives since seafood tends to be priced higher than other proteins. For example, Saskatchewan residents consume seafood below the average Canadian price, suggesting that Saskatchewan households have a consumption flexibility that other provinces (consuming above average prices) do not. Recent years have corroborated the affordability issue in seafood and fires the theory that costs could be partially mitigated if farms were positioned closer to the market than the current Canadian reality. However, in response to the strong sustainability considerations of aquaculture, the industry is expected to grow globally such that, by 2030, 60 percent of seafood will be sourced from farms.

(Please note that from here on, the use of ‘fish farm’ or ‘farm’ refers to salmon farming unless otherwise stated.)

The Document That Started It All…

In February 2023, the federal government announced the closure of over a dozen farms in the Discovery Island region of the Pacific Ocean, finally delivering something close to clarity on the lingering 2019 mandate to transition British Columbia away from open-net pen farms by 2025. Nova Scotia has adopted a similar position toward farming, only approving the lease of two open-net pen sites since 2015, leading up to the 2021 decision to no longer provide lease options. Since the British Columbia statement, their government has remained relatively silent on what the transition plan will be, leaving many fishers confused as to whether or not they should restock their five-year-long operation cycle if the government will force closure post-investment. Federal sources have recently clarified the mandate deadline, instead using 2025 as a deadline for a detailed transition plan for farmers opposed to a closure date, but such has not stopped claims that the progress has been a response to misinformed claims from activists far removed from those truly affected by the decision in (typically lower-income) rural fishing communities, reliant on the industry.

The foundation of this policy comes from the Cohen Commission, a 2012 paper explaining through hundreds of pages all possible contributors to the Fraser River wild salmon decline that was deemed “irreversible;” farming in the Discovery Islands was mentioned by name. There is a lot to critique about the Discovery Island closure mandate, like how unnecessary government involvement has over-regulated the industry to the point of hindering market sustainability, how the evaluation scale of wild salmon populations used to create a national framework does not match national data, or how the report on which the recommendation is based was out of date before government action began. (Although, it appears as though the evolution of Fisheries and Oceans Ministers have since re-evaluated their position toward the aquaculture industry to better assure participants that their decisions are more science-based.) While I am unable to provide full insight into the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, especially given that British Columbian fish farm licenses will not be renewed at the end of June 2024 despite assurances, there are two questions from British Columbian salmon farmers to which this blog may be able to contribute: what information is government using for licensing decisions and is the full range of consequences of this closure decision understood?

Farms are Scary (& Why They Shouldn’t Be)

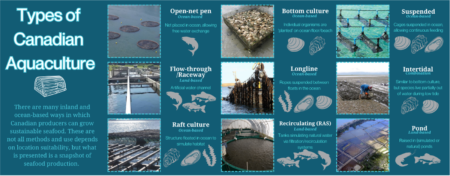

Reducing the risk factor of open-net pen-farmed fish to wild populations can be consolidated into four main suggestions: close farms, move existing farms, reduce stocking density, and transition to inland operations. In an attempt to circumnavigate some of the opinion-based or misinformed slew that exists when researching Canadian fish farms, this section of this blog will address each individually to understand why each suggestion was made and what they attempt to combat for improved salmon health. To begin, it needs to be acknowledged that 50 percent of Canadians do not understand the differences between ocean- and land-based systems (Figure 2) therefore, coming to the table without the information can easily lead to misguided policies. Open-net pen or cage aquaculture involves large pens being submerged in the ocean to provide as close to a natural environment for fish as possible, but it also exposes wild species to farm flows and potential injury from farm gear. The environmental and associated effects on the wild populations of ocean-based farms are the overarching reason for their hatred. Keep in mind, though, that when you see an aquaculture site or pass a fishing community, ocean and population sustainability are at the forefront of farm decision-making regardless of species, not only for the (economic) strength of the community but also in the number of pens that are stocked (which is rarely all pens).

Exposure to proximity-based infestations such as parasitic sea lice is frequently cited as a concern, especially as ocean temperatures increase. Sea lice are not a farmed parasite but a proximity parasite, meaning any salmon that is infected, wild or farmed, can be a transmitter. The stocking density of farms can increase localized exposure then, as wild schools swim past the infected farm, lice can be transmitted through nets; the closer the schools, the higher the risk of transmission. Reducing stocking density or the number of farms (since it also stocking density) would solve some risks however, the positive association of farms to the rate of lice infestations in wild populations is insignificant, ultimately leading to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ classification that farms pose “minimal risk” to wild salmon. The remaining risk can be combatted preventatively and post-infection with antibiotics, but the term ‘antibiotic’ continues to scare consumers into calling for bans, despite research providing assurance of their safety to both the animal and its environment and the recognition that less than five percent of farmed fish are treated using antibiotics.

Another suggestion to benefit wild species is to move aquaculture operations inland, with the idea of land providing a physical barrier to protect from potential farming consequences. There are a variety of ways in which land-based systems can be successful except there will be higher costs and regulatory intervention associated with simulating an ocean environment. Unfortunately, it’s estimated that it would take over a decade for British Columbia to develop and adapt to inland systems, although a widespread industry movement into the coast is not guaranteed to protect wild populations or improve the livelihoods of fishing communities. For example, inland farms require power and energy inputs for water filtration that the ocean doesn’t need. Those inputs come with associated costs and the risk of power interruptions, as evidenced (as a worst-case example) in 2019 by a land-based Florida farm which lost power to their tanks, sadly resulting in the suffocation of 800,000 animals.

The idea that removing farms can improve the dwindling wild salmon population is trickier to address because of the lack of reporting on Canada’s oceans. Keeping salmon stocks healthy is in the best interest of BC because there is no emergent market that can take over if finfish are lost. This was also cited as a major reason for the Discovery Islands closures that have already occurred. Although, whether the historic decline in salmon populations is truly the fault of fishing activities, or if they reflect natural fluctuations in stocks and predation, as seen with mackerel, depends on your information source. While anecdotal evidence suggests Discovery Islands farm closures have returned salmon and other mammals to the region, those in the industry suggest the resurgence of wild populations is more indicative of pens being moved out of migration routes than a benefit of fewer farms. This opinion is subjective depending on which community you speak with, which can also be said about the effects of the Discovery Island closures on Indigenous livelihoods.

Farming Future

Less than 36 percent of Canadians think fish farming is a sustainable food production practice and consumers are also largely removed from the industry. When you look at aquaculture from a sustainability lens, you not only notice the progress the finfish industry has made to improve the size of the industry’s environmental footprint, but also the economic malpractice shutting down fish farms can have. The decades of success aquaculture has in the Discovery Islands has secured coastal farming such that the closure of all sites in and around the area will cost British Columbia nearly a quarter of its salmon industry, future sector investment, thousands of jobs, community mental health, reconciliation progress (depending on the Nation affected), and force the euthanization of over 10 million animals. Simply decommissioning has costs associated that the farmer must shoulder; unless 2025’s transition plan explicitly addresses it, farmers lose their revenue and investments and additionally pay to lose them.

Given the difference in opinion shutting down these farms will have to the surrounding communities, no decision will make everyone happy. Assessing improvements that could benefit local wild populations farm by farm would likely provide a much more thorough policy, as would increased government support for those farms that do need to close or move. Both these ideas would be much costlier for government than a complete regional closure and therefore unrealistic, although would help the lack of data problem in the industry. Regardless, if British Columbian wild salmon and farm interactions can be more currently assessed, there may be an opportunity to better reduce the economic, social, and environmental impacts transitioning away from open-net pens will have.

I hope you’ve enjoyed following me to the coasts – I have enjoyed the opportunity to research a sector I am unfamiliar with and share what I’ve learned. There is no right or wrong seafood purchase if we can be certain that the institutions in place are basing policy decisions, regulatory frameworks, and investment opportunities on current and holistic science. What hinders the growth of the Canadian seafood sector – a vital player in global markets – is the over-prioritization of the sector- or community-removed voices. Here at SAIFood, we want to provide you with as much information to help you make informed food purchases. While I have unlikely answered all of your seafood questions, hopefully, this series ignites a little more thought into the quality that makes it to shelves. Happy fishing!