What would it take to start farming on your own in 2020?

In an industry born on family, tradition, and generational transfer, many farmers have the good fortune to enter an already established farm operation or to receive assistance in establishing their own. Yet, even with assistance, new farmers face financial barriers, so it can be difficult to see how anyone without assistance can enter the industry at all. Farming is not as simple or inexpensive as many outsiders perceive it to be. The costs to purchase or rent farmland, equipment, and other assets are sky high. Taking into consideration yearly input, utility, and financing costs, it can be challenging to make a profit.

In the following article, we will crunch the numbers on what it would take to start grain farming with one section of land (640 acres) in 2020. For reference, Statistics Canada reported that in 2016, the average farm with land in crops was 571 acres, whereas in the Prairies the average farm in crops was ranged between 746-1267 ac. In Saskatchewan, of all farm types, including grain production, more than 55% of all farms are larger than 759 acres.

Fixed Costs

Buying Land

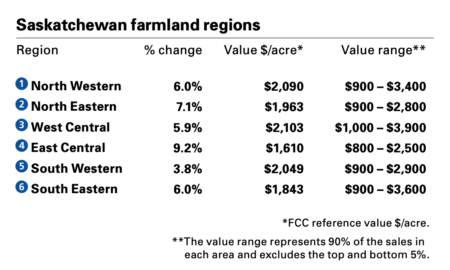

For grain farmers, the most obvious fixed cost is land. Land prices in Saskatchewan have increased by an average of 7.4% over the last 25 years. In 2019, land prices ranged from $1,610 – $2,103 per acre. Taking the average from the six provincial regions, the average purchase price in Saskatchewan would be $1,943/ac or $1,243,520.

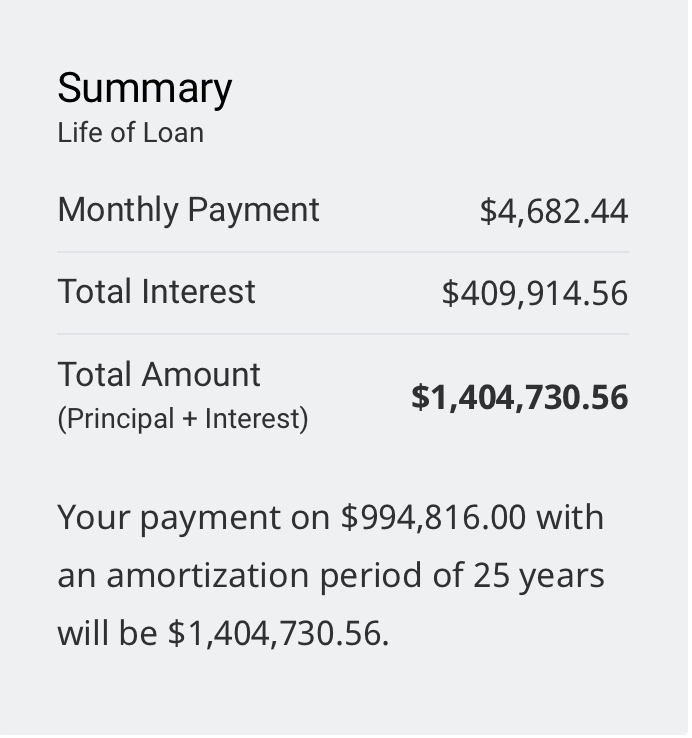

To finance this purchase, we will assume the farmer uses FCC’s young farmer loan. Often, family members are willing to put up land as security to avoid having to make a down payment. To purchase one section of land with a loan of $1.24 million, the farmer would need ~$250,000 in additional land security or a 20% down payment. If the farmer has no land available for security, they have dip into their savings for the down payment of $248,704 leaving $994,816 to be financed.

The remaining cost of nearly a million-dollars will increase by more than 40% thanks to interest rates. Variable closed interest rates for the young farmer loan are currently low: prime + 0.5%. With the prime rate of 2.45%, the loan’s interest rate will be 2.95%. Assuming the farmer takes the loan out for 25 years, using FCC’s loan calculator, the total interest comes to $409,914.56. Monthly payments come out at $4,682.44, totalling $56,189.28 annually. The farmer will also have to pay annual land taxes, which vary by municipality. Using the land price as its value, 55% as its taxable value, and the average Saskatchewan rural municipality mill rate of 13.233, the farmer’s land tax would be $9,051 (Land value x taxable value of land price x mill rate =1,243,520 x 0.55 x 0.013233).

Investing in the equipment to produce and store your crop

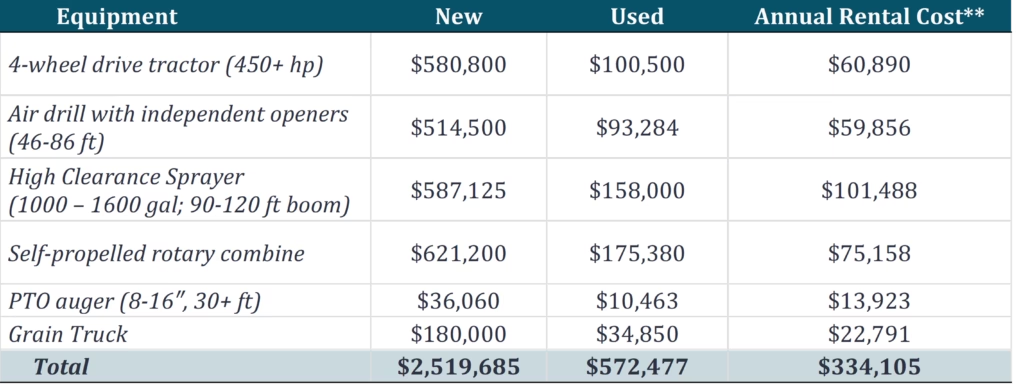

Next, the farmer will need equipment to plant, spray, harvest, and move the grain to market. A farmer has different options for acquiring equipment. For our farmer, we use estimates from the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture’s 2020-21 Farm Machinery Custom and Rental Rate Guide to estimate new purchase and rental costs. Our used equipment prices are calculated using the average of a range of equipment makes, models, years, and hours found on Ritchie Bros. The costs summarized below are rough estimates only. They also do not consider interest on purchase financing, which typically ranges from 3.5-5%.

**Estimated annual hours and rental prices taken from the 2020-21 Farm Machinery Custom and Rental Rate Guide.

Finally, the farmer will need grain bins. Let’s assume the farmer plants 50% canola and 50% spring wheat. Using the SK Ministry of Agriculture’s 2020 Crop Planning Guide, we assume the farmer obtains the average provincial target yields of 50 bushels (bu)/ac canola and 54 bu/ac wheat. Assuming he sells no grain off the combine, he will need space for 16,000 bu of canola and 17,270 bu of wheat. Based on quotes from Grain Bin Direct, the farmer can purchase two 10,700 bu hopper bottom bins for $30,923 each (totalling $61,846) and two 7,820 bu hopper bottom bins for $24,100 each (totalling $48,200), all with delivery and set-up included.

Variable Costs

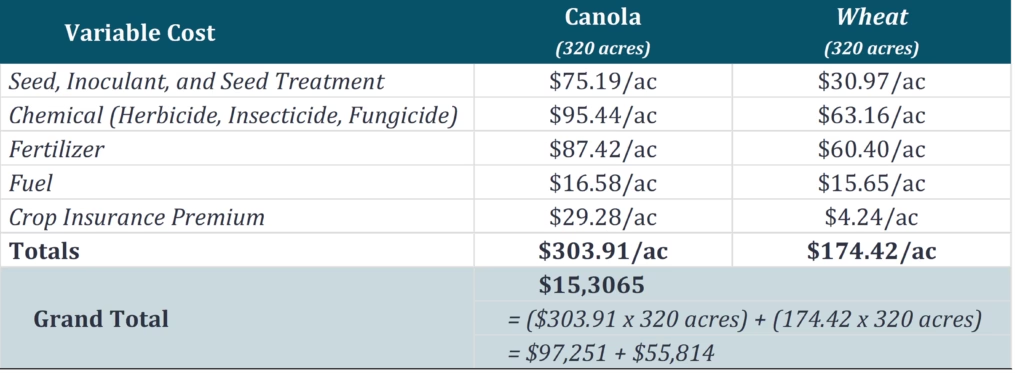

In farming, there are always variable costs to consider as well, which are mostly crop inputs (ie. seed, chemical, fertilizer, and fuel). Once again using Saskatchewan averages from the 2020 Crop Planning Guide as estimates, the following chart breaks down the farmer’s variable costs for production of the 640 acres in 2020:

The variable costs above do not take into consideration farm utilities (natural gas, propane, electricity) nor living expenses, nor a host of other expenses farmers face throughout the year including machinery repair, professional fees, or farm insurance. Personal living, house, and vehicle expenses have also been left out of the calculations.

The variable costs above do not take into consideration farm utilities (natural gas, propane, electricity) nor living expenses, nor a host of other expenses farmers face throughout the year including machinery repair, professional fees, or farm insurance. Personal living, house, and vehicle expenses have also been left out of the calculations.

The Verdict

From the exercise above, it can be difficult to see the feasibility of starting a new farm. Considering the yields assumed above and average grain prices from the Crop Planning Guide ($6.42/bu for spring wheat and $10.70/bu for canola), the farmer’s revenue would be $110,873 from wheat and $171,200 from canola, totalling $282,073. After paying for the variable costs, the farmer has $129,008 leftover to cover land and machinery payments. Furthermore, extra expenses such as a Quonset, farm truck, and tools were not accounted for in this breakdown. It is not hard to see that even with top-end yields and high grain prices, the farm would find itself deep in the red for many years. Perhaps starting a farm alone in the traditional sense is not even possible today. However, starting small and taking advantage of innovative opportunities or niche markets might lead to success.

There are numerous examples of new farmers finding success. One young farmer from Winnipeg broke into the organic hemp market with only 80 acres, and is now growing his organic farm year by year. Another young Ontario farmer is starting a farming co-operative with other young farmers, allowing them to share the capital outlay. New farmers may also consider working for a local farmer or custom farming, offering farming as a service to other farmers, for a few years. These opportunities allow them to develop skills and build relationships with other farmers before starting out on their own. Finally, maintaining an off-farm job full-time or throughout the winter might provide the additional cash flow stability needed to get started.

Overall, this brief cost breakdown illustrates that starting up a traditional grain farm without any assistance or support, even a relatively small one, would be a huge challenge. Yet, the growing popularity of niche products grown on small farms opens up another avenue for new farmers. Though it may be more difficult now than ever before to break into farming, there are ways for innovative entrepreneurs to overcome seemingly impossible barriers and find success by doing what they love: farming.