U.S. organic-backed group targets another Saskatchewan researcher

Written by Kelvin Heppner [su_button url=”https://twitter.com/realag_kelvin” target=”blank” style=”glass” background=”#1ca0e5″ size=”1″ radius=”round” icon=”icon: twitter”]@realag_kelvin[/su_button]

Originally posted on RealAgriculture, May 31, 2017

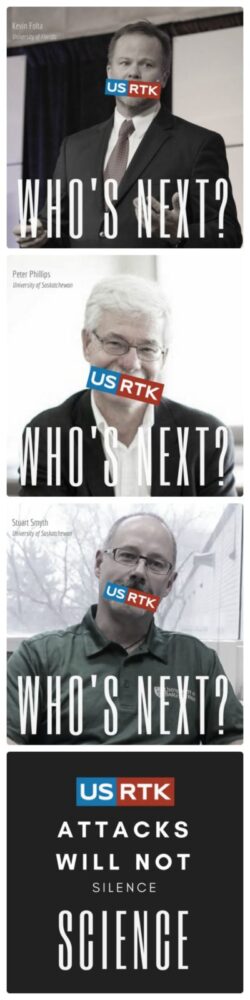

The U.S. anti-GMO activist organization that has targeted several dozen scientists and academics who have published research on the benefits of genetic engineering has set its sights on another researcher at the University of Saskatchewan.

The U.S. anti-GMO activist organization that has targeted several dozen scientists and academics who have published research on the benefits of genetic engineering has set its sights on another researcher at the University of Saskatchewan.

On May 18th, the school received a legal request from U.S. Right to Know (USRTK) to review emails sent by Dr. Stuart Smyth over the last three and half years.

Smyth is an assistant professor who holds the title of Industry Funded Research Chair in Agri-Food Innovation in the College of Agriculture and Biosciences at the U of S. Much of his work has focused on the impacts of genetically modified crops.

According to Smyth, the public records request listed 17 companies and organizations and 11 individuals. Any correspondence with these people and companies must be turned over to USRTK.

It’s the same template USRTK, whose largest donor is the Organic Consumers Association, has used against more than 40 academics and scientists since the organization was formed 2014. This list includes Dr. Kevin Folta of the University of Florida, Dr. Alison Van Eenennaam at UC Davis, and Dr. Peter Phillips, Smyth’s PhD supervisor at the U of S.

The group obtains access to emails sent by scientists who work at publicly-funded universities through public records requests, and then selectively shares pieces of this correspondence with media, often without context, in an attempt to damage the individual’s reputation and portray their work is corrupted. (In the U.S., the requests are filed under the Freedom of Information Act or FOIA, which is why it’s referred to informally as being ‘FOIAed’).

Given his role as an industry-funded chair, Smyth says they’ll find plenty of emails sent to people in private industry. Information on the sources of his research funding, which if coming from government and other granting agencies often requires some private matching, is already posted online and publicly accessible, while his published research is subject to blind peer review, he says.

“With everything being fully transparent and in the public domain, it starts to look like this is a witch hunt to try to put an individual academic in a negative perspective given that they simply have emails to private companies in the agricultural industry,” he says.

Smyth compares it to the approach used by “big tobacco” decades ago.

“In the 60s, when the surgeon general came out and said there was a link between smoking and lung cancer, the tobacco industry got together and did exactly what the big organic industry is doing. They set up a shell institute and they funded this institute heavily to go attack the surgeon generals, medical doctors and scientists who were doing research in this area. This is exactly a 100 percent mirror image of what the organic industry is doing today,” he says. “They’ve set up this shell group and a bunch of attack dogs to go around and start picking off academics and scientists that publish anything about the benefits of GM crops and biotechnology.”

To counter, Smyth suggests governments and agencies that distribute grants, as well as research universities, need to do a better job communicating how their research is funded, the role of private partners, and the benefits of this research and funding.

“Research now is a network of partners,” he says. “Universities need to start communicating how important it is to have research funded through these partnerships, how many graduate students are coming from developing countries, and what the benefit is for these young people to go back to their home country…”

The U of S must provide USRTK with Smyth’s emails in the next few weeks. Assuming USRTK follows its previous pattern, he says he anticipates potentially seeing media reports based on his emails this fall.

Stuart Smyth joined us on RealAg Radio to discuss USRTK’s request for his emails, and the impact public records requests have on researchers working in the area of biotechnology and food:

Corporate funding of university research and its potential to bias that research is a legitimate concern.

Thanks for the comment Paul. We are complying with the demands of funding agencies like NSERC and Genome Canada as applying for a grant to either of these agencies requires anywhere from 25-60% matching funding to submit. The ag industry has funded research at the U of S College of Agriculture and Bioresources for decades in terms of new plant variety development and animal feed trials, so the university has a long history of industry relationships. Your claim of industry bias suggests something troubling in that you are insinuating that the peer review process for journal article publication is faulty. Governments have shared the cost of research funding with industry and as academics we adapt to this situation to undertake research of a more applied nature. This has advantages and disadvantages, but it has increased the amount of research funding available in Canada and this is a good thing.

I said that there is a POTENTIAL of bias, which is always true whoever supplies funds. Therefore, I think it is legitimate to raise concerns about this issue, to require transparency and so on.

I agree. There is a real need for granting agencies to step into this debate and explain how science grant applications are structured to encourage collaboration between industries and universities. Hopefully they will step forward and contribute to this discussion.