Part 5: Plot Maintenance and Data Collection

This is the fifth of a series of #LabToField blogs that will explain the yearly cycle of variety development. Click here to read Part 1: Phytotrons, Part 2: Agriculture Greenhouses, Part 3: The U of S Seed Lab, or Part 4: Seeding

The final plot has been seeded and the seeding equipment has been put away for the spring. But while the hectic field season begins with seeding the plots, it certainly does not end with its completion. As soon as little plants begin peeking through the ground, data collection and plot maintenance activities begin. From early spring mornings spent spraying each plot to long afternoons of spent hand weeding, there is minimal downtime on the research farm. The data collection and maintenance activities vary for each breeding program, generation, and desired end-use. In this blog, I will discuss some of the many activities required of the research team throughout the growing season.

Spraying

Immediately following, and sometimes coinciding with the seeding season is the spraying season. The first round of in-crop spray applications are completed to get weed populations under control before they outcompete the seedlings. Often these spray applications are completed in the early morning or evening to avoid the wind and heat. If an overspray is required, meaning that all plots are sprayed with the same chemical at the same rate, a small plot-tractor with a sprayer implement is typically used. However, in herbicide studies, often conducted by crop protection research programs, treatments may vary between plots. In these studies, research teams frequently use push sprayers mounted on bicycle wheels or hand sprayers.

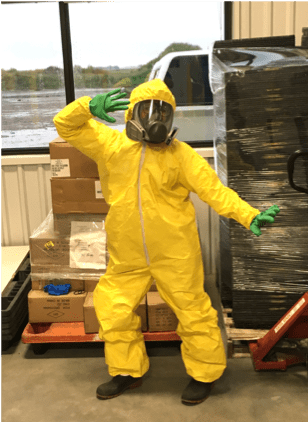

Spray applications conducted later in the season may include fungicides or insecticides to protect against plant disease and unwanted insects damaging the crop. Personal protective equipment required for spraying depends on the chemical and method of application, but typically includes a full-body spray suit, respirator, eyewear, rubber gloves, and rubber boots.

Plot Maintenance

Hand-weeding is required in plots that cannot be sprayed due to crop type, crop stage, or other specified study methods or objectives. Summer students of the breeding and research programs spend many summer days weeding the plots to ensure they remain weed free. Although monotonous, this task requires high attention to detail. Weeders must be able to distinguish between weeds and desired crops so that only those unwanted plants are pulled from the plot. Other plot maintenance activities conducted throughout the year include mowing or rotary tilling around the plots or weed whipper-snipping between plots to keep the area clean. These activities become especially important in preparation for field days or plot visits to ensure the plants and the area around them are looking their best.

Data Collection

Depending on the plant generation, crop type, and breeding goals, the data collection required will vary. Plant counts are conducted early in the season to determine germination and plant density rates. These assessments are completed by counting the plants along a 1m stretch or within 1m2. As the plants grow, heights are measured periodically within each plot. Plant height data helps to select plants that are the desired height of the final variety. Tillers, which are branches located above-ground in cereal crops, and heads, the parts of the plants containing the seeds, are often counted. These counts aid in making yield predictions for cereals. Lodging is a condition which occurs when plants bend at the roots or stems. This affects yield and quality, making the plants difficult to harvest. Therefore, assessments are completed to determine how likely a variety is to lodge in the field. Other evaluations might include recording days to maturity or flowering timing. For programs with the intent of breeding resistance or tolerance to common pests and diseases, disease and insect damage ratings may be conducted.

Yield is one of the most important factors when evaluating breeding lines, as this most directly affects farmers’ bottom lines. Yield is evaluated based on harvested material, which can be collected through mechanical or hand harvesting. Collecting the above-ground biomass is a hand harvesting method which involves gathering all above-ground crop material within a specified area (often 1 m2) in each plot. This material is then dried down and weighed. Samples can be hand-threshed to gather yield data for small plots.

What Comes Next?

Accurate data collection and proper note taking make the selection process possible. Clear and detailed information on each plot’s performance allows breeders and researchers to determine which varieties may be suitable for commercialization and therefore advance to the next generation. After all in-field data has been collected and the plants are reaching maturity, harvesting of the plots can begin. But the breeding work does not end here. Yield data must still be gathered and analyzed, and quality tests at the Grains Innovation Lab must be conducted before final line selections for each generation can be made.

Precise selection of breeding lines leads to the very best varieties advancing to the final breeding stages and ultimately to farmers’ fields for production. This selection process would not be possible without the long hours and hard work completed by the staff of the breeding programs. Their hard work throughout the summer months helps narrow the thousands of varieties at the beginning of the breeding process down to the superior variety for commercialization. As a result, Canadian farmers continue to have new and innovative varieties available to combat the most concerning issues in Canadian agriculture.