Despite having grown up on the West Coast, where I watched crab harvesters pull their traps over the handrails of Sidney Pier, I have no experience with aquaculture. Maybe that doesn’t do me enough justice; I was once mother to a goldfish, appropriately-named Goldy, so I can at least attest that time has been spent fish feeding. Three oceans create the coasts of Canada, I know that much, and yet, some of us would be unable to recognise a shrimp with all its legs attached. Similarly, confusion in and around the industry of ocean sustainability, particularly amongst consumers and those directly involved in the market has increased in recent decades, with the increased dedication to ocean sustainability.

But I had never given fish, on an industry basis, much thought at all. Given the role of fish in the Canadian economy and how full grocery shelves always seem to be, it’s hard to believe. Assuming I am not alone in this oversight, please allow me to impart the efforts of my interests and research. Currently, two-thirds of Canadian seafood is valued in finfish due in no small part to salmon fishing on Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Since the 1990s, Atlantic production has evolved to favour shellfish (like oysters and crustaceans) instead of groundfish (like cod and halibut), introducing increased opportunity and expansion for the harvesting of Prince Edward Island mussels, Newfoundland crab, and Nova Scotian lobster. As of 2021, the Canadian commitment to improving innovation, sustainability, and economic strength has settled the seafood industry to be one generating nearly $9 billion in revenue.

This blog series is meant to serve as an introduction to Canadian aquaculture. As the first of three, this blog is designed to be broad and focuses on an overview of the industry, independent of commercial or farmed methods. Later in this series (for which you hopefully return), I will delve into deeper detail on more controversial and media-involved topics: operational regulations and fish farming. Therefore, while I validate consumer concerns on climate impacts, the ethics of ‘farmed’ fish, and illegal fishing in supply chains, those topics will be covered a different week.

Crash Course on Canadian Fishing

Canadian fishing regulations, very broadly, have two tiers: national and provincial. National programs cover overarching safety and quality standards mandatory for all species and ships like issuing licenses and enforcing proper fishing standards. Provincial regulations, like each one’s Codes of Practice, are then more specific to domestic policies and environmental realities (think: fresh vs saltwater, individual species requirements, movement in and distance to market). Operation matters too, as commercial fisheries must adhere to the laws of international and domestic waters, whereas aquaculture facilities are subject to additional considerations. The Fisheries Act, for instance, is used to create consistency across aquaculture sites but is not so specific as to limit local resource availability of the pen (i.e. which feedstuffs to use). Aquaculture also operates with a five-year production cycle to allow for fish to work through the hatchery, growth, and harvest stages, and operations must be leased and licensed prior to a single fish entering the site.

Despite production and demand peaks in 1999 and the early 2000s, respectively, the resource-based industry is firmly situated in Canada as a provider of healthy, low-carbon protein sources. At least, this appears to be the opinion of consumers, of which 64% claim their seafood purchases are built upon nutrition goals, although the Health Canada food pyramid suggests most Canadians increase weekly consumption beyond the one serving a week average. Largely based on exposure and availability, British Columbians consume the most seafood per week whereas a third of the Canadian Prairies consume seafood weekly, mainly from frozen options. This latter point is hugely important for the fishing discussion as Canada is export- and restaurant-driven, with frozen options dominating local availability due to the shipment (travel) necessities of meat.

Overwhelming Value of International Markets

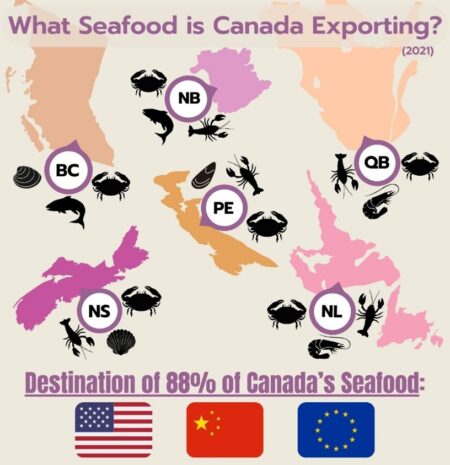

When it comes to seafood, the majority of what is raised/caught locally (80%) is destined for international markets. In response, Canada imports a little more than that with a better variety of choices mainly in frozen products from China and canned goods from Thailand. Later in this series, I’ll go more in-depth about how this relates to Canada being resource-based but requiring value-added or processed products however, for now, what you need to know is that the availability of Canadian seafood products is underrepresented in domestic grocery stores.

The reliance on global markets (Figure 2) stems from the attractiveness of the market. “Market price” written on the bottom of your menu is only applicable to wild-caught fish/shellfish, and reflects the total (subjective) cost of catch, from bait to transport to marketing. To clarify, the 2023 average retail $27.04/kg price tag for salmon is based on the international cost to produce; what you find at stands by the wharf is more likely representative of the effort by the fisher. But, overall, seafood has a higher price than other meats – a price which doesn’t seem as onerous when it’s internationally sourced. The appeal continues when we consider the troubled strength of the Canadian loonie, which improves the potential margin made from the global seafood market (which operates under the American dollar).

Social (Community) Dependence

Beyond the fluctuating price, fishing can be a high-risk industry. Although fishing vessels are independently owned and provide healthy catch competition, the low buyer concentration increases an individual’s reliance on a handful of companies and their agreements. But all fishers are at the whim of natural fish populations regardless of operation size of which, as of 2019, 96% of businesses were classified as small or micro. Part of the reason there are increased calls for audits and vessel reporting is to have a better understanding of current ocean conditions to prevent future declines in sustainability, population levels, and productivity. As an extreme example, the February 2024 closure of the Meteghan processing plant in Nova Scotia was directly related to outdated lobster stock data, which suggested to farmers a prosperous season that was never truly able to be met; the village – recognised as a huge fishing community – will continue to feel the effects.

On a beneficial note, the evolving trend of independent buyers/processors requiring sustainability and welfare standards and encouraging innovation has improved the industry, occasionally to the point that the industry is reliant on fishers. For example, climate change impacts on water quality can lead to increased animal health concerns and stagnant or reduced salmon populations, but a decline in seafood production will lead to job loss, sustainability reduction, and reduce the reconciliation efforts with the Indigenous communities heavily reliant on fish stocks.

The involvement of Indigenous communities is of particular importance not only to coastal diets but to livelihoods, environmental symbolism, and ceremonial values. The share of the seafood quota attributed to Indigenous fishers has increased since the turn of the century as a step toward reconciliation, although the system is incomplete. There exists a moderate livelihood clause in Canadian seafood regulations for Indigenous peoples, wherein species whose season is closed to commercial operations can still be caught if the individual is fishing to provide for the Nation, not to make a profit. However, the vagueness of ‘moderate livelihood’ has only ignited the tense relationship between police officers who believe they are stopping illegal fishing and Indigenous peoples who view the arrests as targeted.

Concluding Remarks

One of the loudest problems fishers have with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans is the lack of reporting that not only affects local communities but also misinforms policy (which, you’ll notice is a major theme in the next two blogs of this series). The aquatic prowess of Canada and its status as a seafood sustainability leader provides major opportunities to further diversify production, innovate aquaculture, better involve Indigenous communities in decision making, and improve overall operational transparency. Adoption of any of these efforts will only serve to strengthen the resiliency of Canada’s seafood economy.