Agriculture Myth Busting

When grocery shelves are so well-stocked, it’s easy to overlook the global food availability crisis. However, Canada is not exempt. The price of land is increasing against the call for greater production quantities, more farms are being integrated into larger parcels operated by bigger producers, and yet, what graces shelves is a uniform set of standards all farmers approach. So how can we be in a food crisis, if every farmer grows the same products and holds them to the same criteria?

Dirt is dirt is dirt… right?

Actually, no. Agricultural soil is a complex physical and chemical equilibrium, constantly shifting with management, the climate, the market, and the presence of insects or wildlife. As of 2023, only seven percent of Canadian land is able to produce food. Of that, only 10 per cent is considered “highly suitable” for crop production. These figures exclude marginal lands which might be used for forage production and/or cattle grazing and come with their own unique set of land considerations which affect soil health and crop productivity.

Soil quality can be sorted into eight different classes based on the impact risks of surrounding factors. No two farms are identical in the challenges they will face throughout the growing year, or the specific advantages they may be able to develop.

Develop is an important undertone in the crop quality discussion, as the determination of land suitability for agriculture, let alone to which farming type, can only ever be described as “potential”. For instance, land that can produce may be unavailable for fields, or they can produce but it is not recommended to do so for one reason or another. Therefore, as food demand and production change over time so, too, will soil properties and potential land availability; improving crop availability and quality is not simply a matter of increasing production.

Making the Grade

Determining what makes it to the consumer varies depending on where you’re looking. What is universal, however, is that farmers strive for the highest quality crop possible, in part because high quality grain earns more at the elevator. Elevators, through the Canadian Grain Commission, grade the incoming product based on a national set of standards created by and reported back to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). These guidelines segregate crop species and assess for size, weight, foreign materials, pest damage, and infection percentages. Coincidentally, in response to farming innovations and production improvements, the CFIA recently updated standards for the first time in 40 years.

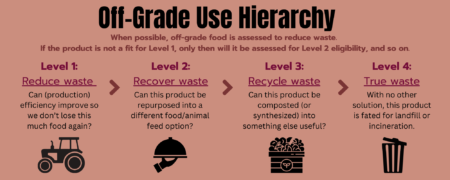

Off-grade products are then assessed through a network to eliminate wasted crops (Figure 1). Anything that cannot be marketed into a usable product is considered a food loss, although the quantity that is lost from food supply is difficult to narrow, since it is often lumped into broader ‘food waste’ figures.

Salvaged grain for animal feed must go through its own set of guidelines for both quality and quantities to reduce potential toxin contamination and acidosis. This practice can have huge cost implications for farmers, as observed in 2023, when Agriculture Financial Services Corporation doubled their feed salvage allowance for the year to avoid the number of acres farmers would otherwise have to abandon in response poor growing conditions. When analysed to ensure grain meets livestock nutritional needs, food processing by-products can adequately replace more costly feed grains.

The Produce Challenge

Standards for both product appearance and the ways in which food is produced can affect the end product similarly to how climatic events may affect harvest. As recent years have exemplified, labour cannot always be effectively or efficiently substituted in production agriculture and downstream processing. Supply chain shortages in the labour-intensive fruit and vegetable industry, for instance, have led Canadians into a period of produce availability shortages. The fragility of fruits and vegetables suggests that mechanization is an incomplete substitute to human labour and can damage the product. Therefore, in the presence of human resource issues, harvest delays can harm crop quality, reducing product payout if it can even be salvaged for grocery shelves.

Typically, off-grade produce can be repurposed into compost, processed foods, or, occasionally, supplement animal feed. While food rescue programs and the invent of in-store ‘ugly food’ brands such as Loblaw’s Naturally Imperfect can reduce some of this waste, it is important to note that salvage programs are incomplete solutions to the food waste crisis. The unsatisfying truth is that most unmarketable, irregular fruits and vegetables (i.e. those blemishes on produce that grocery stores reject) are destined for landfill. Cases exist where some of Canada’s abundant unused food can be fed into the livestock industry, however with more of a farmer finds program mentality rather than an overall improvement to the problem. In order to approach meaningful food waste reduction, produce grading standards may need to be updated to better reflect increased consumer apathy toward product appearance (although that is a discussion for a different blog).

Concluding Remarks

Despite strict limitations as to which crops can compensate which end-use markets, Canadians have lost confidence in Canadian food quality in recent years. In current times of inflation and global political discourse, we, as consumers, are starting to see the effects of inconsistent food supply chains. The Rogers Sugar workers’ strike in autumn 2023 and subsequent sugar shortage is an extreme but no less relevant example of how the end user can be impacted by upstream disruptions. Having to throw away produce you could have sworn was still days ahead of its best before date (also known as shelflation) is one day-to-day observation of markets stretching costs and quality limitations to meet demand.

Although we are unlikely to see every kernel of grain in some kind of bag on grocery store shelves, hopefully this blog has highlighted some of the reasons for that trend. The stringency of standards to which food is held – arguably, too restrictive – suggests very little allowance for non-uniform products to enter the same market. Alternative markets provide opportunity for more acres to be salvaged and for fewer edible products to end up in landfill; however, no two plots of land are identical. There is reason for products to be rejected and, unfortunately, not every acre of Canadian land is food-producing.