Agriculture Myth Busting

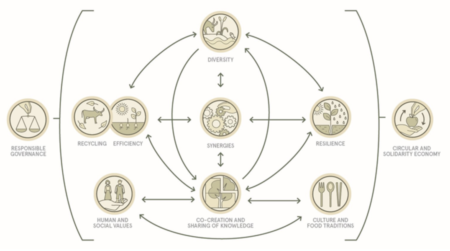

There currently exists a global land competition problem. In the current trajectory, North American agricultural productivity will be facing very real challenges in the coming years, as the average Canadian diet requires nearly 130% of domestic agricultural land available (or, nearly 81 million agricultural hectares since Canada currently operates with 62 million hectares). Increased risk aversion in farmers and correlated farmland price increases suggest that expansion is unrealistic. Therefore, with a growing population and associated needs, humans are tasked with making more out of less available land. What little land remains unoccupied tends to be insufficient for crop production or too costly to convert to food production. Some land competition can be attributed to food-fuel tradeoffs (bioenergy crops are typically more resilient than food crops on poor-performing fields), nonetheless, Canada has spent the better part of the 21st century converting twice as many acres away from cropland as it restored.These trends appear to be on par with specific agricultural challenges since the 1950s such as stricter soil science and classifications as technology advanced, and that value is lower than the average of G20 and European countries. However, it is predicted that global land-use shifts will need to take place to adequately meet the 2030 United Nations climate and productivity goals. One option that this blog will attempt to summarize is the idea that livestock production is taking up valuable crop space and therefore acres are distributed inefficiently; as a result, the absence of livestock will free land such that the growing population (and food security) needs can be met. It is important that land be assessed holistically in order to best allocate available resources, as the availability of natural resources impacts managerial requirements and mitigation capabilities. Assessing what is feasible in a field via potential soil impacts is more important than trying to find a plot that fits management, especially given the potential that management decisions are one of the reasons for poorly-producing agricultural soils. Therefore, an agroecological approach is promoted (Figure 1) to accommodate productive limitations and assess all resource efficiency options.

It is important that land be assessed holistically in order to best allocate available resources, as the availability of natural resources impacts managerial requirements and mitigation capabilities. Assessing what is feasible in a field via potential soil impacts is more important than trying to find a plot that fits management, especially given the potential that management decisions are one of the reasons for poorly-producing agricultural soils. Therefore, an agroecological approach is promoted (Figure 1) to accommodate productive limitations and assess all resource efficiency options.

Marginal Land, Decent Opportunity

Generally, marginal land refers to that which is unsuited for sustained agricultural production. Approximately 10% of all agricultural land is classified as ‘marginal.’ It is the sustained technicality in that definition that separates marginal from unproductive: marginal lands can be improved to be productive but its limited productivity can also be worsened. The restoration of marginal status to an agriculturally productive one is a lengthy process as, really, farmers are building land capability rather than guaranteeing performance. Performance is rarely guaranteed in agriculture. Similarly, productivity improvements are not ensured and sustainable land use (i.e. effective/efficient resource distribution; efficient land use) does not ensure climate sustainability.The complexity of soil suggests that best management practices can only ever improve potential. Using marginal land not only increases the number of arable acres available for food production (effectively improving land use efficiency, when executed appropriately) but also improves soil quality and carbon sequestration potential, though not immediately. To clarify, cropland – even well-performing cropland – has the lowest average soil carbon sink capacity amongst land types. Creating permanent cover on those marginal lands ultimately builds the soil nutrition and biodiversity networks that can support future crop production; the degree and speed to which these effects improve a farm is dependent on management and species selection. For example, adding nitrogen to a field reduces the sink capacity by about 11% while applying nitrogen with phosphorus only reduces uptake by about 5.7%. If every acre of marginal Canadian land were to be replaced by willow trees to improve sequestration capacity, the nation could theoretically offset 8% of our greenhouse gas emissions. In many ways, the marginal land use discussion is one indirectly linked to climate change opportunity, which, in turn, prompts the conversation in a livestock direction.