Why growing farm sizes are normal

Why growing farm sizes are normal

Frequently when I tell someone I’ve just met that I’m an agricultural economist, the conversation almost always involves some version of ‘aren’t big farms bad?’ My answer is usually a sigh and a ‘No’. But why do people ask this question about farm size? Let’s look at why big farms aren’t as bad as one might think, and why we have more and more big farms.

Why small isn’t best

I will agree, small farms sound ideal and quaint like some people think they should be. Personally, I’d love to own a small plot of land (a quarter or two) to grow crops or maybe have pasture for animals. In reality, this is very difficult to do and be profitable. But why? The answer is competition and economies of scale.

First, suppose you’re a small beef producer with 100 other producers in your community. In a competitive market, cattle buyers seek the lowest price. If one of your competitors needs to improve their cash flow, they may choose to sell their cattle just above the cost of production, let’s say $195/cwt. This creates a local market where everyone else will have to sell at that price or hold their cattle longer, costing more money. In truth, most farmers are price takers, not setters.

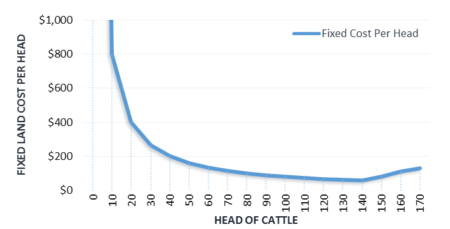

In any business, there are fixed and variable prices. Variable prices, such as labour or capital, increase as the level of output increases. Fixed costs (like pasture) are independent of output and remain constant, and can greatly impact your unit prices. If your pasture cost is $8,000 per year, pasturing 40 cattle makes the cost per animal $200. However, if you could keep 60 cattle on that same pasture, your cost per head decreases by a third to $133. Economies of scale are “proportionate saving in costs gained by an increased level of production”. If you are able to sell your cattle at $220/cwt, 40 cattle may have cost $190/cwt to produce, whereas, 60 animals would reduce costs per cwt to $184. Economies of scale allow you to profit $6/cwt[1].

In any business, there are fixed and variable prices. Variable prices, such as labour or capital, increase as the level of output increases. Fixed costs (like pasture) are independent of output and remain constant, and can greatly impact your unit prices. If your pasture cost is $8,000 per year, pasturing 40 cattle makes the cost per animal $200. However, if you could keep 60 cattle on that same pasture, your cost per head decreases by a third to $133. Economies of scale are “proportionate saving in costs gained by an increased level of production”. If you are able to sell your cattle at $220/cwt, 40 cattle may have cost $190/cwt to produce, whereas, 60 animals would reduce costs per cwt to $184. Economies of scale allow you to profit $6/cwt[1].

The corporate side of farming

Farming is a business. As such, all businesses need to profit from their production. Post-WWII, there was a need for improved crops and yields. Farmers were seeking better solutions such as higher-yielding, fewer pests, weeds and diseases, and the ability to process more in less time. Improved crop genetics greatly contributed to this, as did equipment advancements, allowing farmers to farm more land in the same amount of time. In the 80s, the elimination of government subsidies forced the entire agriculture industry to become more competitive, and high-interest rates pushed many surviving farms to adopt a business-like approach to the operation of their farms. In 2011, 45% of farms in Canada were corporations, predominantly multi-generational family-owned corporations.

It costs money to make money

Just because some people aren’t on the large-scale farming band-wagon, doesn’t mean farmers shouldn’t profit from getting larger. Agricultural goods, for the most part, do not sell at high premium prices. That’s because most agricultural products need to be processed. Consumer don’t buy a whole cow from the farm, they buy cuts of beef at a grocery store, canola is crushed into oil, cotton is spun into a textile[2], and wheat is processed into a flour which then goes into multiple different products. If raw agriculture goods were priced higher the value-chain markup price would be too high for the final consumer to buy. If a producer stays small, they likely need to position themselves somewhere in the supply chain where consumers are willing to pay higher prices for smaller scale production and stay profitable.

Small is good, but big doesn’t mean bad

To all the smaller producers out there, kudos to you. And to all the larger farmers, congratulations for making it in the competitive world of agriculture. In either scenario, it mustn’t be easy competing in the industry, carrying the financial risk of your business and keeping up with the ever-changing industry and economy. No matter your scale, farmers are trying their best to stay in the business while producing quality goods. It doesn’t matter whether it’s by going big or specializing on a smaller scale, as long of the products continue to be in demand, are affordable, and are safe, as consumers we shouldn’t judge how farmers choose to produce.

[1] If all your animals were feeder steers at 500 lbs, with 40 cattle you would profit $6,000 ($150/steer) and 60 cattle would profit $10,800 ($180/steer).

[2] Raw materials make up only 66% of the total cost of fiber or yarn for textiles. Once it becomes a fiber or yarn, it still needs to be processed into a textile through multiple technical steps.

Pingback: Getting Big Isn’t A Bad Thing - SAIFood