By Kinga Nolan

B.Sc. in Agriculture, 2022

Consumers are bombarded with various labels and claims every time they visit a grocery store. Unlike the colour of a banana or the marbling of a steak, which can be assessed easily in-store, most food labels signal a credence attribute – factors that cannot be evaluated even after the purchase and consumption of the product (Hobbs, 2021). Two of these federally regulated labels include the ‘Product of Canada’ and ‘Made in Canada’ labels, which came into effect in 2008. The Product of Canada label implies the item is produced using virtually all (at least 98%) Canadian ingredients and manufacturing. Conversely, Made in Canada labels have no relation to Canadian ingredients; instead, the final manufacturing process occurs in Canada, and the label must include a qualifying statement indicating the ingredient origin (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2019b). Given that these labels use relatively similar terminology yet have vastly different definitions, do consumers understand the regulatory difference between them? Moreover, given that consumers are exposed to many different labels every week, are these labels even important to consumers?

Consumer Survey

To answer these two questions, we surveyed a representative sample of five hundred Canadians in January 2022 for my undergraduate honours project. The survey was divided into four sections: consumers’ knowledge questions regarding Product of Canada and Made in Canada labelling terminology; a choice experiment to compare the relative importance of 13 food labels, including Product of Canada and Made in Canada, as well as altitudinal and demographic questions.

Label Importance and Understanding

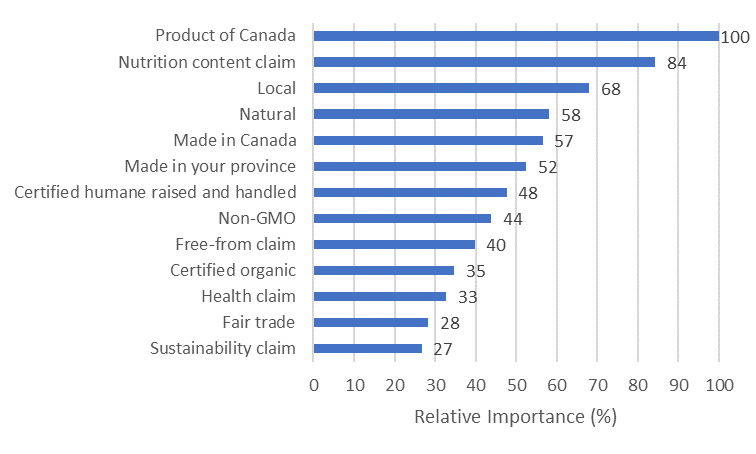

Of all those surveyed, Product of Canada ranked as the number one most important label in the choice experiment, while Made in Canada ranks fifth, as seen in Figure 1. We found that older consumers, those from the prairies or who live in rural areas, were more likely to value Product of Canada over younger individuals or those who live outside the prairies or in an urban area. This relationship might be because the Prairie, rural, or older individuals may have stronger ties to agriculture and their local economies. When it comes to those more like to value the Made in Canada label, it tended to be men and lower-income consumers than women and consumers with higher incomes. While both these labels of Canadian food packaging ranked relatively high in importance, the survey showed that most consumers had poor regulatory knowledge of these labels. One-third of the sample was able to identify the correct regulatory definition of Product of Canada, and only one-quarter could identify the Made in Canada definition. In total, only 6% of the sample could correctly identify both definitions. When considering the high importance of Product of Canada and Made in Canada labels in conjunction with poor regulatory knowledge, this suggests that consumers might have a stronger affinity towards the “Canadianess” of the label instead of what the label means.

Other Relevant Labels

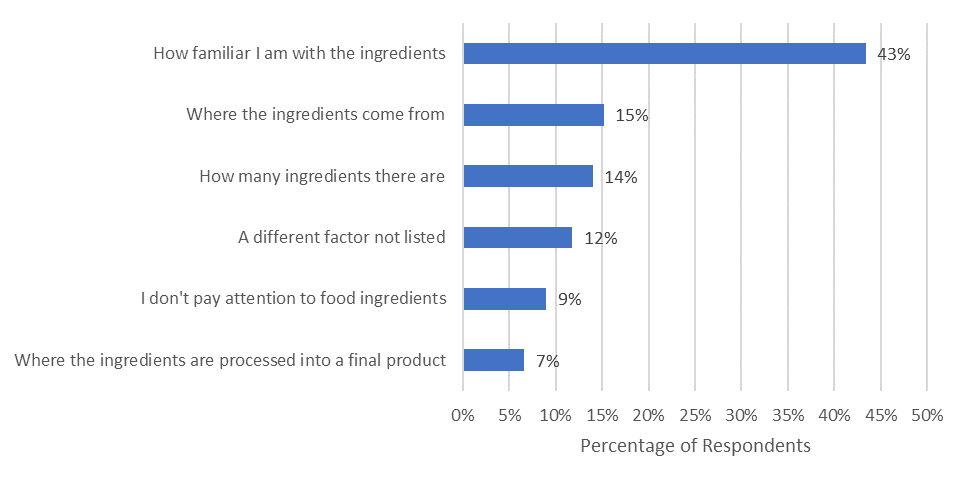

We also surveyed the most important factors to consumers regarding food ingredients. Overwhelmingly, the most popular response was “how familiar I am with the ingredients”, as displayed in Figure 2. Although consumers ranked Product of Canada and Made in Canada highly in the choice experiment displayed in Figure 1, which relates to the origin of ingredients and manufacturing, these were far less important stated factors regarding food ingredients displayed in Figure 2. This suggests there is a disconnect between what consumers believe is most important about food ingredients versus what a label is indicating to consumers. Given the rise in dietary restrictions and trends like “clean eating” or “pronounceable ingredients”, consumers may be paying more attention to what the ingredients are and whether they are familiar with them. In recent years, consumers have also been encouraged to pay closer attention to food labels as they pertain to ingredients because they are interpreted as healthier or safer choices. This could indicate why “nutrition content claim” and “natural” ranked relatively high in the choice experiment, shown in Figure 1.

Moving Forward

The findings of this study suggest that there is confusion over what the current domestic labels signal, yet ingredient origin is perceived to be an important factor to consumers. Therefore, our government institutions may consider implementing a new labelling policy with more straightforward terminology that can be understood by the population that indicates what foods contain predominantly Canadian ingredients.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is already proposing changes to the current Product of Canada and Made in Canada labels. The CFIA proposes reducing the threshold of ingredients for Product of Canada from 98% to 85%. Whereas, Made in Canada labels would no longer require a qualifying statement indicating the origin of the ingredients (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2019a). Yet, given the results of this study, consumers are already confused about the meaning of these labels. The current changes, especially regarding the Made in Canada proposal, may only be more confusing. The CFIA could consider other proposals to clarify these terms to consumers, such as implementing standard symbols and colours for domestically produced products and more apparent terminology such as “Grown in Canada”, “Manufactured in Canada”, and “Grown and Manufactured in Canada”.

Canadian Food Inspection Agency. (2019a). Comment on: Proposed changes to guidelines for “Product of Canada” and “Made in Canada” claims. https://inspection.canada.ca/about-cfia/transparency/consultations-and-engagement/product-of-canada-and-made-in-canada-claims/eng/1558707125531/1558707125782

Canadian Food Inspection Agency. (2019b). Guidelines for “Product of Canada” and “Made in Canada” claims. https://inspection.canada.ca/food-label-requirements/labelling/industry/origin-claims-on-food-labels/eng/1393622222140/1393622515592?chap=5

Hobbs, J. E. (2021). AREC 398 – Food Economics and Consumer Behaviour. Module 1, Lecture 2. University of Saskatchewan. Accessed via Canvas Learning Management System.

Kinga Nolan

Kinga Nolan was awarded her Bachelor of Science in Agriculture (Honours), majoring in Agricultural Economics in the Spring of 2022. She is a 2017 Schulich Leader and an avid community leader in agricultural advocacy and civic engagement. Kinga will attend the University of Calgary this fall to attain her Master of Public Policy. She intends to use this education to improve agricultural policy and public relations and intends to serve as the federal Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food one day.

We would like to thank Kinga for sharing today's article with SAIFood. The results of this article come from her undergrad thesis 'The “Canadianess” of a Label: Consumer Perceptions of the Product of Canada and Made in Canada Food Labels', supervision of Dr. Jill Hobbs.