We forgot to ask the staple crop, cassava, how it was doing. Now we have damage control to do!

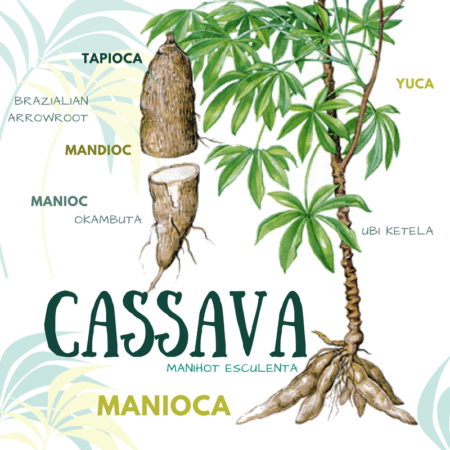

Are you familiar with Cassava? You may know cassava as yuca, manioc, mandioca, and you may have eaten it if you’re a tapioca fan (YUM!) or have ever tried a bubble tea. For those unfamiliar with cassava, it’s a starchy tuberous root eaten globally. Cassava is a staple food, in Sub-Saharan Africa, but also gaining popularity in developed nations as an alternative ingredient in foods. Despite its importance and gains in popularity, this crop has nearly been forgotten by crop researchers and was recently facing the threat of production losses due to disease, pests and genetic decay.

Are you familiar with Cassava? You may know cassava as yuca, manioc, mandioca, and you may have eaten it if you’re a tapioca fan (YUM!) or have ever tried a bubble tea. For those unfamiliar with cassava, it’s a starchy tuberous root eaten globally. Cassava is a staple food, in Sub-Saharan Africa, but also gaining popularity in developed nations as an alternative ingredient in foods. Despite its importance and gains in popularity, this crop has nearly been forgotten by crop researchers and was recently facing the threat of production losses due to disease, pests and genetic decay.

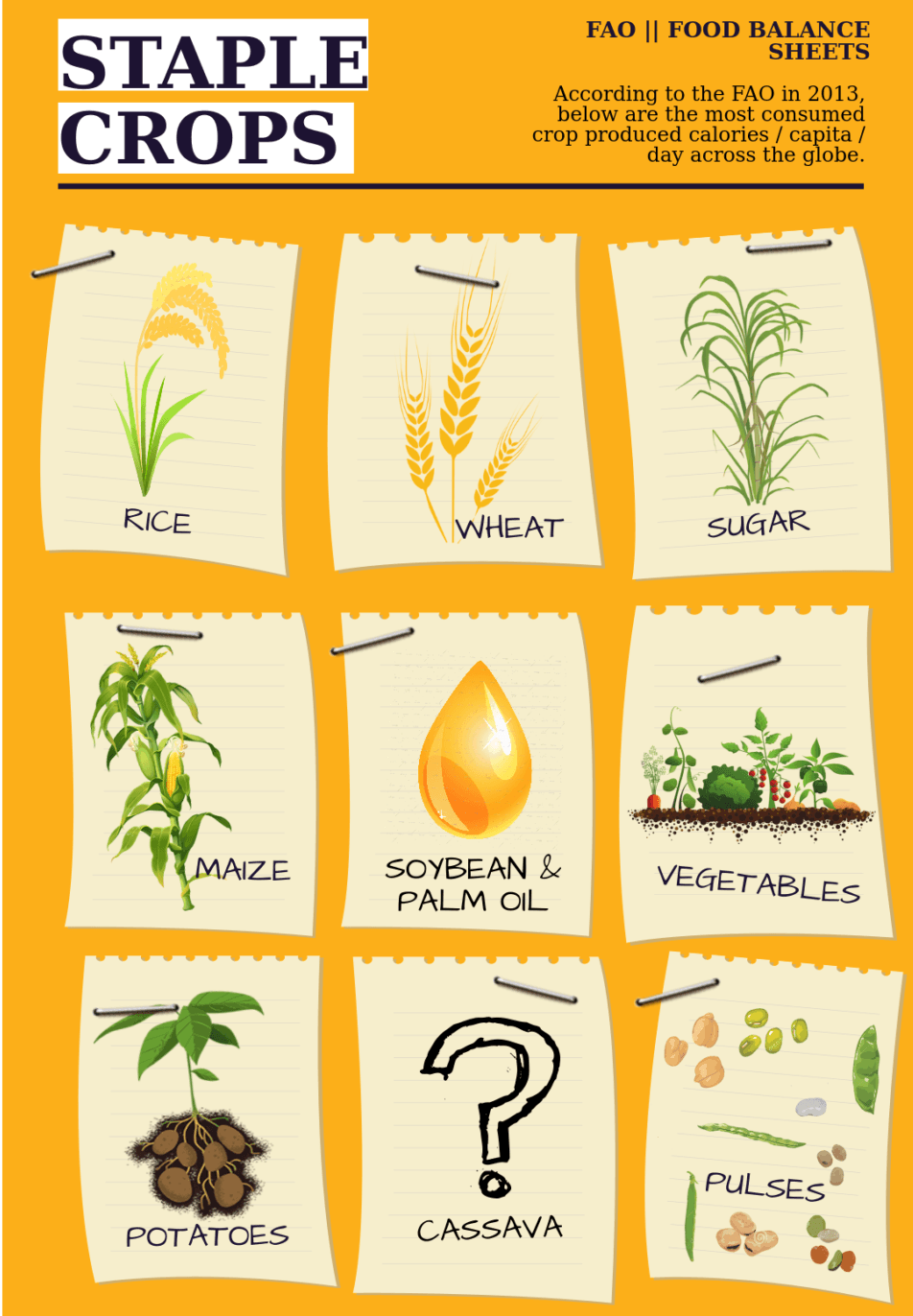

This crucial crop has been under-researched for too long. Other staple crops such as wheat, maize, rice, and sorghum benefit from extensive research funding and the time has finally come for cassava.

The forgotten staple

In 2013, the Food and Agriculture Organization reported in their food balance data that cassava provided the 13th highest calories/capita/day (37 kcal) in the world and was the 4th most consumed calories among cash crops. On the African continent, cassava is the 9th leading source of daily calories at 159 kcal/capita/day, in which Middle Africa averages 357 kcal and Western Africa at 248 kcal.

In 2013, the Food and Agriculture Organization reported in their food balance data that cassava provided the 13th highest calories/capita/day (37 kcal) in the world and was the 4th most consumed calories among cash crops. On the African continent, cassava is the 9th leading source of daily calories at 159 kcal/capita/day, in which Middle Africa averages 357 kcal and Western Africa at 248 kcal.

Of the 255 million tonnes (mt) produced in 2013, 101 mt were used as food, 87 mt as feed and nearly 31 mt were lost due to weather, pests/diseases, and waste/spoilage. Considered an essential crop by the FAO, the losses of cassava production are alarmingly high at 11% compared to other staple crops such as maize (0.4% production loss) and wheat (3.9%). The African continent produced 53% of cassava stocks in 2013, consumed 61% of all cassava’s food stocks (24% of all production) and accounted for 69% of the losses. There is an issue with the production of this staple crop.

Is Cassava an important crop?

Cassava has become a staple crop because it’s a very tolerant and inexpensive crop. This perennial shrub native to Latin America is conditioned to grow in sub-tropical climates. Not only is resistance to drought, but it also produces vegetables in marginal soil conditions, requires relatively few and inexpensive inputs and the plant can be propagated to produce more plants through a steam clipping. Not to mention, the tuberous root has long-term storability in the ground, if conditions are not ideal to harvest or store above ground.

Is it too late to care about the risks?

As a staple food to more than 7% of the world’s population, cassava is a significant crop, yet until recently little research had been conducted. While the demand in developed and developing nations grows (as do producer prices), cassava is facing numerous issues and risks.

Grown in a tropical climate, cassava is at risk of numerous diseases and pests. Given its long season compared to other crops, this extra environment exposure increases the risk of disease and pests destroying the crop. While there are several diseases we could cover in this blog from blight to virus transmitted by whiteflies, mealybugs and nematodes, many of these can be treated through crop rotations, drainage, and the use of chemical applications (if available). What is not as easily controlled is the genetic decay of the crop.

Genetic Research

Cornell University, through a number of its branches and affiliated research organizations and programs, has begun cassava crop research. Cornell’s Institute for Genomic Diversity has found that the use of plant propagation from steam clippings rather than seeds has caused genetic decay of the species. The lack of sexual reproduction has resulted in a buildup of contaminant prone genetics making it more susceptible to diseases and pests.

Through Gates Foundation and UK Department for International Development funding, Cornell has been able to begin the Next Generation Cassava Breeding Project (NextGen) to improve cassavas breeding stock and “unlock the full potential of cassava.” Through genomic and phenotypic data and access to cassava germplasm from around the world, NextGen is dedicated to ensuring cassava remains a staple food. They also aim to improve the breeding cycle through shortened cycles, improved flowering and seed set, and increased photosynthesis efficiency.

Since the domestication of plants, we often interrupt the cycle of their ecosystems to fit our ecosystem needs, and sometimes we forget to ask “Comment ça va?” How are you doing? Now, researchers are doing just that for the cassava plant.

A little bit more about cassava

- Poisonous yet delicious! The cassava tubers contain cyanogenic glucosides (cyanide). Sweet varieties have lower levels, whereas, the table varieties are bitterer and only edible after they have been cooked or processed. Cassava plants also contain linamarase, an enzyme that helps break down the cyanide.

- According to International Market Analysis Research and Consult, the 2016 cassava starch market was 7.3 million tonnes and since 2009 has been growing annually by 2.2%.

- Growth as alternative starch within food products and non-food goods such as paper products, textiles and glues.

- Cassava can be made into flour or a bio-fuel.

- Caribbean governments have recognized cassava to be a crop and an import that could greatly reduce their food import bill and be used as a substitute in value chains rather than other domestic crops.

- Nigeria is the largest producer of cassava. In 2013, FAO reports that Nigeria produced 18% of all cassava equal to 47.4 million tonnes.