In a perfect world, food production would have no impact or cost on the environment or biodiversity. However, this world only exists in fairytales and environmental non-governmental organization campaigns. The stark reality is that food production has always impacted its surrounding landscapes and always will. This is because when food is produced, ecosystems are changed, there has to be a trade-off made. However, agriculture has made great advancements toward ensuring that the production of food has less of an impact on biodiversity than in previous times.

As part of the international discussions on the environment, climate change and biodiversity preservation, in 2022 the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was established. The GBF calls for 30% reductions in many factors impacting biodiversity to be realized by 2030, based on 2020 conditions. As part of the strategies to reduce the negative impacts on biodiversity, there is a call for greater regulation and reductions in the use of vital crop protection products, like herbicides, fungicides and insecticides. While reduction of the products would be successful in meeting the mandates, it would fail to be productive economically. Reductions in the use of these products would reduce yields, resulting in higher rates of global food insecurity. In many aspects, there is a complete lack of methods and metrics capable of assessing biodiversity changes, let alone quantifying any change.

There is No 'Natural' Food Production

All the food items in grocery stores – meat, dairy, produce, and dry and canned goods – come from managed food production systems. These systems range from expansive farming operations covering tens of thousands of acres such as is the case with cattle and wheat, to smaller operations such as is the case with poultry and orchard fruits. Farming operations increase the efficiency of production, reducing waste in the transportation of food from the farm to the store shelf. Yet, all of this food production impacts biodiversity.

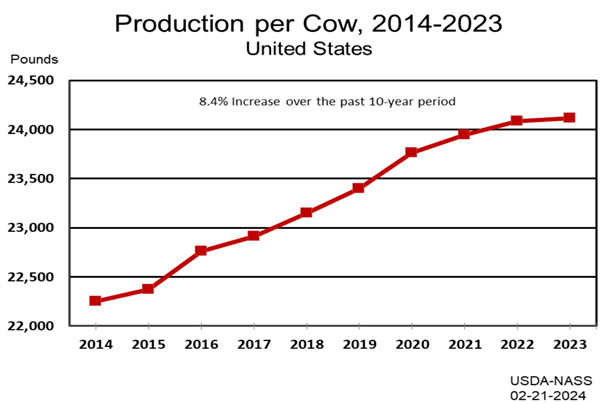

Managed food systems are increasingly efficient concerning food production, as is demonstrated in the figure below on the amount of milk produced per cow in the USA. The increased production efficiency contributes to helping ensure food price increases are as low as possible. The increased production per cow, also means fewer resources are required to produce a gallon of milk. Thereby these production gains are reducing the need to bring more land into cultivation to produce livestock feed or to pasture livestock, contributing to reducing the impacts of milk production on biodiversity.

Some may argue scavenging for food is a natural means of feeding oneself, however, this is only an option for a very niche part of society. Scavenging is only capable of providing a fragment of total nutritional requirements and is not a viable option for everyone, not only will you be missing some nutrients, you will lose a lot of time trying to live off the land. This is how our ancestors lived thousands of years ago, before the domestication of crops, when the average lifespan was 30 years of age.

Defining Impacts on Biodiversity

Developing a comprehensive metric to assess the complete impact of food production on biodiversity is impossible. Such a task would require accurately measuring changes in all living species of mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, fungi, bacteria, soil microbes, viruses, etc, so metrics can be developed to assess specific components of biodiversity, such as impacts on birds or aquatic life. While these targeted assessments provide one perspective, they fail to account for important but tangential changes. An example is the change in wetland areas, where overall wetland areas may be reduced due to farmers draining these lands, and an assessment could conclude this was harmful to bird biodiversity. However, these types of analysis fail to consider the additional amount of food that is now able to be produced and the benefits that come from the increased food production. There is not likely a benefit-cost analysis’ taking place for each farmers decision to drain a wetland on their land. Alternatively, many farmers have cleared trees, shrubs and bushes from their farmland. Some will view this as reducing the habitat for birds and other wildlife, however, these views fail to consider the reduced amount of GHG emissions from farm equipment that no longer has to take extra time to constantly travel around small areas of trees. An additional trade-off would be whether a small number of trees sequester more carbon during a year, than the thousands of crop plants that would be growing in the same space.

Changes in land use impact biodiversity. If land is deforested to be used for livestock or crop production, biodiversity will change. Similarly, if land once used for crop or livestock production is purchased to be part of a protected biodiverse area, changes will again occur. The challenges for assessing impacts on biodiversity from land use change are illustrated in this example. Suppose an area of land is clear of trees, containment basins for water will be created and the land is used for livestock production. This change could negatively impact populations of larger mammals such as moose, elk and deer. This change could positively impact changes in the number of wetland birds using the created water reservoir or grassland mammals such as antelope. Trying to create a metric that would meaningfully compare potential declines in large mammal populations to potential increases in aquatic bird populations is extremely difficult requiring many assumptions, that may, or may not, have sufficient data to verify the assumption. Any outcome would be a subjective opinion of the individual undertaking the evaluation, highlighting the challenge of obtaining truly objective assessments.

Some ecologists are beginning to advocate for invasive species to be considered part of biodiversity and allowed to remain, even though they may be causing significant economic and environmental harms and potentially reduce the production of food. This highlights the gaps in agreement as to what should be considered to be part of a specific biodiversity area and how to robustly assess changes that benefit or harm biodiversity.

Ways to Meaningfully Benefit Biodiversity

Evidence indicates that over time, innovations provide products and processes that contribute to reducing the impact of food production on biodiversity. It’s vital for policy makers and those involved in the negotiation of new environment or biodiversity agreements to acknowledge that innovations in agriculture commonly take 20 years to reach peak adoption. Suggesting that agriculture could achieve 30% reductions based on 2020 circumstances between 2022 and 2030 is naïve.

Agreement negotiators that advocate for biodiversity protection need to be more cognizant of the fact that altering biodiversity impacts food production and the relationship to reducing food insecurity. Policies and regulations enacted based on the GBF calling for reductions in crop protection products or the use of crop nutrients, will reduce food production, thereby increasing the number of food insecure.

Certainly, protecting biodiversity is important, but it is even more important to ensure that children aren’t needlessly dying from food security as world and life changing future innovations may reside with a present food insecure child. Investing in our future means that every measure possible is taken to reduce food insecurity.