Unpacking the BC Tree Fruit Co-op Closure

Picture this…

It is the last week of July 2024. The Okanagan is the hottest it has ever been, and fruit production has never been lower. For months, the future of your orchard has been uncertain, at best, and now the fruit packing house that you and your grandparents have used every summer for decades is no longer in operation. Just weeks ahead of what is expected to be a meagre harvest, you now must find a new distributor.

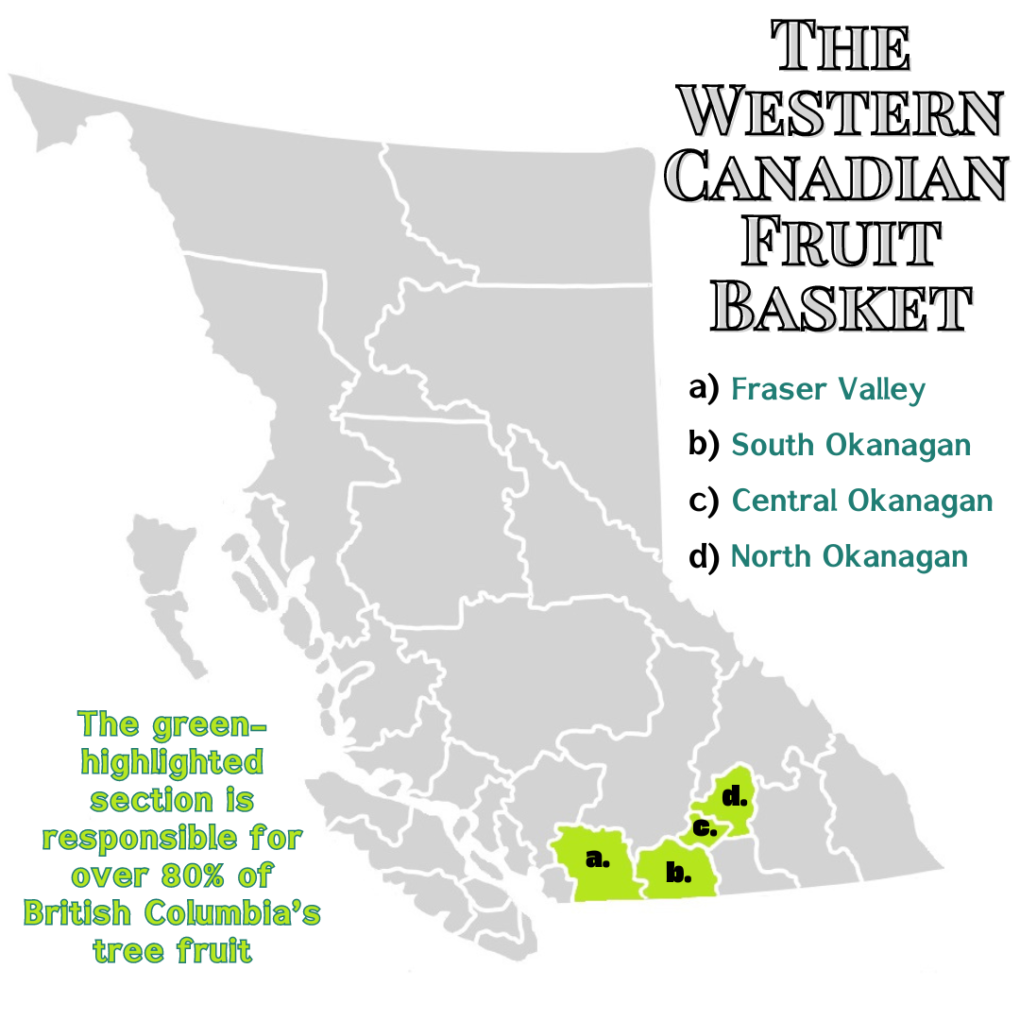

This was the reality for over 200 fruit farmers across British Columbia (BC), blindsided by the dissolving of BC Tree Fruits Cooperative (BCTFC) during what was meant to be a recovery year, albeit with not much hope. The official notice by BCTFC cited poor weather conditions for bringing in low predicted fruit volumes, and the market movement of the last few years (specifically the lack of improvement) as reasons for the closure. With such broad reasons behind the decision, I thought it was worth writing about not only what happened with BCTFC but also where BC’s turbulent fruit industry has been left following a volatile summer.

How Bad Was 2024?

Back in 2021, BC was burning and underwater. Following a devastating heat dome situation that sent the Okanagan into drought conditions, much of the Fraser Valley was flooded, forcing rebuilding which, at the time, was predicted to take the blueberry industry at least 10 years. (It is worth pointing out that most fruit trees, including the ones discussed throughout this blog, do not produce fruit until they are three years old, with the tree’s full productive potential not usually reached until years later.) Although the BC Provincial government launched the Fraser Valley Flood Mitigation Program to help alleviate the financial losses and predicted repair costs from the atmospheric river, devastating winter conditions later that year would mark the official downturn of BC fruit production.

The BC fruit producers weren’t able to catch a break, yet Canadian consumers didn’t seem to notice. This is because fruit producers in the East would not face nearly as difficult production conditions or market volatility as observed in the West, which partially explains how grocery stores were able to supplement produce departments with Canadian fruit. The sacrifice consumers made was with quality opposed to price, as it was the western fruit prices that spiked in response to low fruit numbers, not the entire industry. With all this, more bad luck was headed West. Winter conditions are notorious and recurring adversaries to fruit production, which is typically reserved for winter temperatures that do not decrease past -20 degrees Celsius. A series of excessively cold winters and extremely hot summers has unfortunately led to a decline in fruit and fruit farmers. Take peaches, for instance, which are well-known and in hot demand across Canadian summers; in roughly the same cultivated area, peach production decreased in the last three years, forcing the price upwards. Apples and grapes have faced much less market success in terms of the number of acres and the value of what is produced has declined particularly hard after the weather events of 2021. Cherry value and production have risen however, this past year’s winter likely stopped that progression. It is the stacked impacts of multiple low-revenue years that have likely contributed to the Okanagan grower loss that is so heavily noticed in the community today.

December 2023 was uncharacteristically warm even by BC standards, meaning stone fruit bulbs never fully settled into winter dormancy (the plant equivalent of hibernation). The cold snap in January subsequently killed off those bulbs, leaving approximately a third of Okanagan cherries viable for summer fruit production. By March 2024, stone fruit was predicted to be only 10% of a normal harvest year and by early July, BCTFC would discover their apple intake would be less than half of what was needed to remain operable.

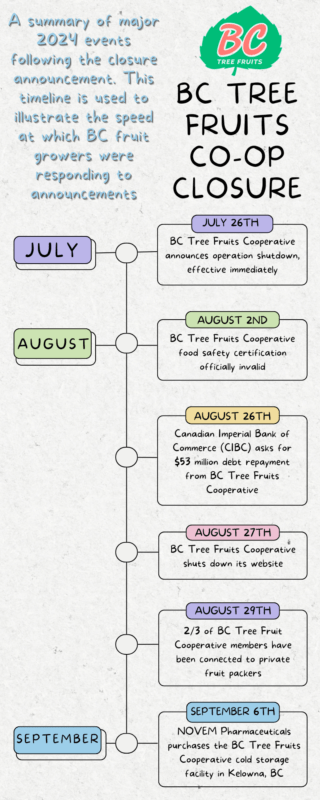

Missing Packhouse

On July 26th, 2024, BCTFC informed shareholders it was insolvent (the value of BCTFC assets was insufficient to cover costs and shareholder requirements), officially launching the cooperative into a “restructuring grace period” to allow for the collection of as much capital as possible to redistribute amongst shareholders.  At one time BCTFC owned over $100 million in fruit assets; as of September 2024, they owe over $53 million. Beyond money, BCTFC had strong roots in the Okanagan since its establishment in 1936, for its grower support, bargaining power, and infrastructure. Infrastructure is particularly important going into fall because of cold storage, whereby approximately half of harvested fruit (particularly apples) is set aside for up to 10 months to continue respiration and heat formation, so those bins can be released to market later in the year. This is part of the reason we can see apples in the grocery store year-round while softer fruits, like peaches, tend to be released seasonally. Although initially appearing as the end of a single business, the closure of BCTFC has wider-reaching market implications.

At one time BCTFC owned over $100 million in fruit assets; as of September 2024, they owe over $53 million. Beyond money, BCTFC had strong roots in the Okanagan since its establishment in 1936, for its grower support, bargaining power, and infrastructure. Infrastructure is particularly important going into fall because of cold storage, whereby approximately half of harvested fruit (particularly apples) is set aside for up to 10 months to continue respiration and heat formation, so those bins can be released to market later in the year. This is part of the reason we can see apples in the grocery store year-round while softer fruits, like peaches, tend to be released seasonally. Although initially appearing as the end of a single business, the closure of BCTFC has wider-reaching market implications.

Without adequate fruit storage, orchardists in the area are predicting a handful of outcomes which, when compounded, may make a real dent in the BC fruit market. Growers can rely on private packers (as recommended by the Agriculture Ministry of BC), although there are concerns over the facilities’ capacity (likely able to receive and store less than BCTFC could) and the receivers’ commitment to farmers when pressured by its shareholders. The alternative is growers may approach harvest with a “why bother” attitude, foregoing the costs of hired labour, picking, storage, transport, and marketing, instead allowing apples to rot in the orchard. Doing so, while a farm-specific decision, risks flooding the market with imported fruit if adopted by numerous farms, driving Canadian prices and grower participation down, or pushing more Canadian product into the processed/juicing chain. Conditions like this have already been observed in BC, in June 2024, when, to meet consumer demand and maintain the market, fruit stands began importing from Washington State (and some were not as transparent about that as necessary). On a positive note, it appears as though these were worst-case scenarios; by the beginning of September 2024, most growers had found receivers for their fruit and the company that purchased the old BCTFC facility, NOVEM Pharmaceuticals, announced it would keep cold storage facilities open this year. While this alleviates some stress for this year, the future is still uncertain as NOVEM plans to develop regional storage infrastructure such that fruit growers in the area can self-stabilize, without the need for the old BCTFC site resources after this season.

The Sector's Financial Trellis

Financially for BCTFC and its debt repayments, the future is uncertain, now that they’ve reached the end of their restructuring period. This isn’t the first time BCTFC has been in trouble with growers due to their poor planning – a common adversary to the risky nature of cooperatives. In 2022, farmers protested the lack of transparency and forward-thinking in the cooperative following the closure of two northern Okanagan facilities in favour of a new development in Oliver, BC. The BCTFC board of directors barely survived a vote for their dissolvement and a year later, they were sued by one of their contracted cherry packers for withheld payments over a disagreement with food safety certifications.

Financially for BCTFC and its debt repayments, the future is uncertain, now that they’ve reached the end of their restructuring period. This isn’t the first time BCTFC has been in trouble with growers due to their poor planning – a common adversary to the risky nature of cooperatives. In 2022, farmers protested the lack of transparency and forward-thinking in the cooperative following the closure of two northern Okanagan facilities in favour of a new development in Oliver, BC. The BCTFC board of directors barely survived a vote for their dissolvement and a year later, they were sued by one of their contracted cherry packers for withheld payments over a disagreement with food safety certifications.

One positive outcome of the BCTFC closure is how hard it impacted the farming community that the Provincial Government of BC stepped in, increasing the AgriStability (an optional government risk management program producers can purchase) compensation rate and cap, establishing the Tree Fruit Climate Resiliency Program to alleviate the capital costs of appropriate projects, temporarily amending the Agricultural Land Reserve rule that limits where fruit can be processed. The combination provides short-term and long-term options for a community already uneasy about available financial support. The $70 million orchard/vineyard replanting program update has been critiqued as an incentive to stay in the industry rather than a subsidy to give growers a head start. Similarly, the overreliance on crop insurance in the last four years counters how insurance mechanisms are designed (i.e. not for frequent repeated use).

Unfortunately, it appears as though we are in a wait-and-see situation, although this next year will be very telling of how BC’s fruit industry rebounds. There is opportunity but there are also barriers to maintaining orchards, especially after all the surprises the industry has recently faced. The government’s call for resilience to both an uncertain market and worsening climate conditions may not be viable for some growers. In the case of BC fruit, BCTFC’s closure may be a much-needed push for industry change, if an adequate leader can step in with sustainable improvements and producer support.