Agriculture Myth Busting

In 2014, Canadian fast food chain A&W, aggressively launched a campaign announcing they were only purchasing antibiotic- and synthetic hormone-free animal products for their restaurants. The campaign decisions were reportedly backed by independent and national research, simultaneously preying upon consumer uncertainty regarding antibiotics and the increasing consumer preference for ‘antibiotic-free’ labels. (It may be worth noting that this switch came at the expense of sustainability, as 95% of the beef served in A&W restaurants, at the time, was sourced from Australian and American farms.) Nonetheless, other chains such as McDonald’s later boarded the same train, opting for antibiotic-free nuggets in response to the label’s success in the industry.Health Canada identifies six overarching themes that contribute to Canadians’ aversion to antibiotics, highlighting potential human health/safety risks and the lack of transparency between supply chain partners as major contributors to public concern. However, when one considers the realities of hormone and antibiotic use in animals – why they’re used, how, and the risks to people – it becomes clear that fast food marketing tactics built upon keeping the public in the dark about Canadian agriculture, actively misrepresent production realities in favour of profit. The use of antibiotics are vital for maintaining animal health and welfare, the absence of which (situation dependent) can violate animal welfare laws. The strict regulatory process for hormones similarly suggests adverse effects on the environment when producers refrain from using them.

A brief history of additives

Antibiotic and hormone use in agriculture has not always been as regulated as it is today. Since their initial use in the 1970s, where zero regulation was in place to ensure proper handling, administration, and dosage, the use of non-medicinal antibiotics has declined. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency now operates a more stringent research and regulatory process to approve anything injected/fed to the animal, ensuring animal and animal product clearance before the product gets to shelves, but there is also a tighter list of approved uses. While those steps target the consumption end of the supply chain, there are also best management practices outlined for administration to guarantee animal safety and additive-specific safety.Consumers care a great deal about their food purchases. Between rising food costs and food availability concerns, individuals still want to know that the animals that produced their meat, their eggs, their milk, were ethically raised and humanely treated. However, confusing language in regulations have led to different interpretations of the guidelines, fractionating the level of trust consumers have in antibiotic and added hormone use on farms and allowing fear-monger tactics (regardless of if that was the intent) to shape the direction and perceived ethics of food purchases.The issue with antibiotic and hormone use in Canadian agriculture should be focused on misuse or overuse of these products, as opposed to a definitive aversion to both. Further, it is perhaps unfair to even group the two together, as their purposes and risks are not uniform across animals and products. Therefore, while the overarching fear lumps hormones and antibiotics together, the remainder of this blog will address each separately to provide a clearer picture of their uses in Canada.Additional Hormones

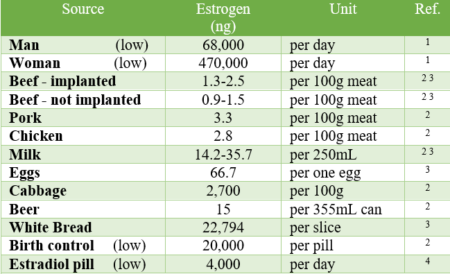

Fundamentally, the use of the label ‘hormone-free’ is wrong; no chicken, pig, or cow are without naturally-occurring hormones required for normal body regulation. Therefore, companies use the phrase “raised without the use of added hormones” to clarify instances where zero additional hormones or beta-agonists (growth promotants that stimulate muscle growth) are given to the animal from birth to slaughter (including omitting their use from the mother while she’s pregnant and pre-weaning). So, the question remains: if hormones are naturally-occurring, why are synthetic hormones used in livestock?First, it’s important to know that synthetic growth hormone use is not as prevalent in the Canadian food system as “free-from” labels would have you believe. Canadian pork is raised without the use of growth hormones; the same is true in Canadian chicken, where growth hormones have been banned since the early 1960s. While synthetic hormones like recombinant bovine somatotropin (rBST) have been proven to increase the volume of milk produced in cows and are used in the United States today, Canadian regulators noticed an associated increased infection risk and banned growth hormones from dairy nationally.The main use (and consumer fear) of hormones occurs in the beef industry, where hormonal implants are often injected in the ear, and both directly and indirectly encourage weight gain. These hormonal gains directly occur by stimulating muscle growth and indirectly when their use improves feed efficiency. Improved rate of gain means fewer days until the animal is market ready which, in turn, has environmental implication. An implanted beef steer, for instance, requires 19 per cent less land and generates approximately 18 per cent fewer greenhouse gas emissions than those raised without. Similarly, fewer inputs such as feed and water means a more cost-effective package of meat on grocery shelves. The absence of hormones could subsequently worsen an already sensitive environmental position and increase the price of beef.

1 Jeong et al. (2010)

2 Alberta Beef (2016)

3 Canadian Animal Health Institute (2021)

4 Tomlins (2019)

Antibiotic Fear

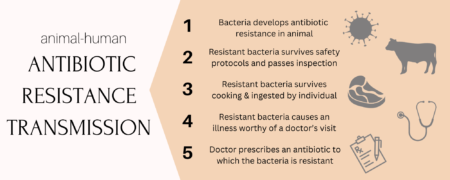

It can be argued that antibiotic use has the potential to be a health concern if they’re improperly used. Barrett et al. (2021) suggest that most people associate ‘livestock antibiotics’ with ‘factory farm’ and, subsequently, ‘poor welfare.’ In reality, antibiotic use is commonplace in agriculture, used to treat, control, and prevent disease, and heavily monitored by the Canadian Food Inspection Industry. Similar to the way people use antibiotics to care for their pet or child, farm animals may be prescribed antibiotics when their health is at risk. Not to mention, in Canada, it is a crime to willfully ignore health concerns in sick animals. Therefore, farmers and ranchers use antibiotics to ensure sick animals recover as quickly as possible, simultaneously mitigating the spread of disease that may affect other members of the herd.Ionophores – the antibiotic commonly associated with growth promotion – is the only antibiotic category used designed for feed efficiency as of 2016, however, unlike medicinal antibiotics, ionophores are voluntary additives. The approved use system is so rigorous, there are regulations for drug approval, veterinary distribution, and on-farm administration on a federal level, with Saskatchewan being the only province without additional provincial standards. It is because of the strict monitoring/testing of our inspection agencies that all products available for purchase are antibiotic free meaning what you are buying does not contain antimicrobial residues. Beyond defining set withdrawal periods to ensure the antibiotic has been sufficiently removed from the body to not be transmissible in animal products, if a tested sample does detect trace amounts of residue, the load is discarded and farmers are fined for antibiotic misuse. Meat processing plants have officials that test carcasses to check for the presence of antibiotics, thereby ensuring that meat free of antibiotics is strictly complied with.These monitoring systems become even stricter when producers are opting into “raised without the use of antibiotics” labels as it must be ensured that zero antibiotics, from birth to slaughter, have been given to the animal or its mother. If antibiotics are required at any point (e.g. alternatives are insufficient to combat a given disease), farmers must comply, and that animal is removed from the ‘raised without’ stream and cannot be marketed as such. In the absence of preventative drugs, farmers often reduce their animal load, implement strict biosecurity methods, and adapt feeding to better diversify healthy gut bacteria (i.e. adding probiotics), all of which are encouraged in conjunction with antibiotics to maximize animal health and welfare.Although there is a prevalence for antibiotic-free goods, the increased interest in so-called quality assurance labels in the last decade has not translated to a decline in antibiotic use. The human concern and risk appear to be with the volume of antimicrobials purchased nationally. As discussed on the Food FOCUS Podcast back in 2019, the size of livestock means more antibiotics are required on a weight basis in order for the product to be effective, which may cultivate an environment where bacteria can (although very, very unlikely) adapt, mutate, and potentially become drug resistant.Antibiotic resistance from livestock is extremely improbable, and the risk of resistance transfer to humans who may consume tainted products is even lower. The maximum residue limits that exist per drug, per animal ensures that human gut biomes will not be exposed to antibiotics to which bacteria can become resistant. Campylobacter– one of the leading bacteria groups transferred from pork that can cause intestinal distress in humans – is, on the high end, estimated to pose an infection threat in Besides, the pathway to infection from meat is long, and contingent on a string of rare instances happening together (Figure 1). While some of this is thanks to the types of drugs used for livestock which, for the most part, cannot be and is not used in human health, there also just hasn’t been any evidence that what little antibiotic resistance that exists in livestock is a threat to humans.