Let’s Talk Farming Series

Saskatchewan farmers rely on a vast toolkit of technologies to produce their crops every year. Farming practices are always changing, and innovation and adoption of new technologies are vital to improving agricultural efficiency, productivity, and sustainability. This is the second in a series of blogs, #LetsTalkFarming, that will dive into some of the important technologies used by Saskatchewan farmers and discuss the current issues surrounding them. Read the first blog on fertilizer use here.

What's the Scoop on Pesticides?

Pesticides are an important tool for Canadian farmers to help grow high-yielding, high-quality crops. They are used to combat insect, disease, and weed pressure, all of which can cause harm to farmers’ fields. While pesticides are highly regulated by Health Canada, issues such as the increasing resistance to herbicides in weeds and the ever-present public pushback against the use of chemicals like glyphosate raise concerns for farmers over what the future of Canadian pesticide use might look like.

Pesticides in Canada

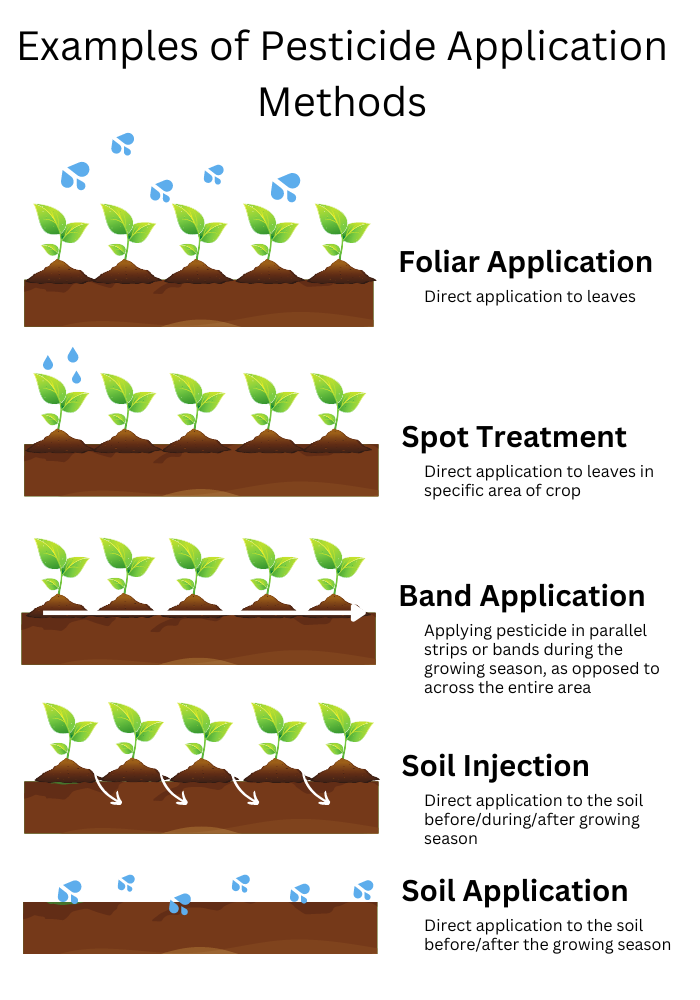

There are three main kinds of pesticides used by farmers as part of their crop protection strategy: herbicides which are used to kill unwanted weeds, fungicides to protect against plant diseases, and insecticides which are used to protect plants from insect damage. Pesticides can be applied in many different ways, including foliar application (spraying pesticide onto the leafy part of a plant), soil application (applying pesticide to the soil rather than the plant), soil injection (using pressure to apply pesticide under the soil), band application (applying pesticide in parallel strips), and spot treatment (applying pesticide to small, distinct areas).

In Canada, pesticide use is strictly regulated by the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA), a division of Health Canada. Canada’s PMRA is one of the most robust pesticide regulatory systems in the world. Before pesticides are authorized for use, the PMRA must ensure the product is safe for humans, animals, and the environment, ensure the product is effective for its intended purpose, and set maximum pesticide residue limits allowed in food. On an ongoing basis, the PMRA re-evaluates pesticides, reviews company sales and incident data, and monitors compliance, ensuring that once pesticides are registered for use, they are continued to be used safely. Internationally, Canada’s regulatory system is held up as a gold standard for its science-based decision-making.

Threats to Future Glyphosate Use

Despite Canada’s stringent regulatory system, public perceptions of chemical use are not always positive. This is particularly the case when it comes to glyphosate (well known as RoundUp), one of the most important herbicides in farmers’ toolkits. Because glyphosate is a non-selective herbicide, meaning it kills broadleaf and grassy weeds, its uses include pre-emergent applications or in-crop applications with a herbicide tolerant (HT) crop such as canola or soybeans. Through its efficient weed control, glyphosate, combined with the use of complementary HT crops such as canola, has helped farmers reduce tillage and summerfallow practices, and until recent price hikes, was relatively inexpensive. Glyphosate is one of the most studied pesticides in the world and also one of the safest, having a lower toxicity level than items such as vanilla and caffeine. In 2017, Health Canada re-evaluated glyphosate and confirmed its safety, stating that “[n]o pesticide regulatory agency in the world currently considers glyphosate to be a cancer risk to humans at the levels at which humans are currently exposed.”

Even without scientific evidence connecting glyphosate to cancer or other health concerns, there is a global push to ban glyphosate, and the list of regions with restrictions or bans on the use of glyphosate continues to increase. In Canada and the U.S., glyphosate is approved and supported for agricultural use. However, even in Canada, eight out of ten provinces have some form of restriction on the non-essential, cosmetic use of glyphosate. North American companies are also taking note of public concern over the use of this chemical. In 2020, Kellogg’s announced it would be phasing out the use of pre-harvest glyphosate in its wheat and oat supply chains. Some farmers worry that this is just the beginning of restrictions on their ability to use glyphosate within their operations. In the EU, the current glyphosate approval expires at the end of 2022. The European Federation of Food, Agriculture, and Tourism Trade Unions is one of many organizations calling for a ban on glyphosate.

Herbicide Resistance a Growing Concern

Not only are farmers facing the potential issue of reducing or phasing out glyphosate from their production, but another problem causing headaches for Canadian farmers is herbicide resistance in weed populations. Herbicide resistance refers to a plant’s ability to survive and reproduce after a herbicide application. In Canada, the first herbicide resistant weed was reported in the 1950’s. Herbicide resistant weeds cause huge problems for farmers because of the need for increased herbicide use and decreased crop yield and quality. The estimated cost of herbicide resistance for Canadian farmers is between $1.1-$1.5 billion annually.

There are multiple weeds with resistant populations in Saskatchewan, including wild oats and green foxtail, but kochia is the biggest concern. Aside from the resistance issue, kochia is a problem weed for farmers because, as a tumbleweed, it spreads seeds easily. In 2019, a post-harvest survey in Saskatchewan found that out of 283 kochia populations, 88% showed some level of resistance and 23% demonstrated high levels. Not only do prairie kochia populations show high resistance to group 2 herbicides, but resistance to group 4 and group 9 herbicides is rising as well. Chemicals are placed into groups according to their mode of action to kill the intended target. Globally, weeds have developed resistance to 21 of the 31 different sites of action. This growing resistance is alarming for farmers who already struggle to control populations in their fields. To reduce the risk of herbicide resistance development in weeds, many chemicals now include a mixture of modes of action.

Chemical Use and Environmental Stewardship

According to Canada’s Pesticides Indicator, which evaluates the relative risk of water contamination by pesticides, pesticide risk has been increasing since 1981. Yet, most Canadian land is at low or very low risk. The Prairies have a higher percentage of agricultural land treated with herbicides and fungicides compared to Eastern Canada, but so far the risk is considered low on the Prairies because of the dry climate. Increases in prairie pesticide use can largely be attributed to the shift away from conventional tillage towards no-till systems, which has contributed to increased carbon sequestration and improved soil quality. In conventional no-till systems, weed control is achieved mostly through the use of pesticides. Fortunately, the most dangerous pesticides have been replaced with relatively safe, environmentally benign pesticides, leading to an overall reduction in the risk from pesticide use.

In response to concerns over herbicide resistance, environmental contamination, harm to pests’ natural enemies and non-target organisms, and outbreaks of pests that were formerly suppressed, the integrated pest management (IPM) approach to crop protection has evolved. The IPM approach combines chemical, mechanical, behavioural, biological, and cultural pest management approaches to respond to pest problems with the most effective, least-risk option. This means that action is only taken to control pests when the acceptable threshold of pest damage or risk is exceeded, as opposed to applying pesticides on a routine basis. Through careful planning, identification, and monitoring, farmers make crop protection decisions to control and prevent pest problems in the most economic, efficient, and environmentally sound way.

Where Do We Stand with Pesticides?

It is important to remember that Canadian farmers are human too. They want a safe and healthy environment for their families. Our farmers value the health and quality of their land not only for economic purposes, but so that future generations have the opportunity to farm as well. With the strict oversight of the PMRA, pesticide use in Canada is extremely safe, and constant innovation within the pesticide industry continues to provide safer and more effective options.

Roughly 44% more Canadian farmland would be needed to produce the level of grain our farmers currently grow without pesticides and other biotech crops, such as HT canola. Despite concerns of public pushback against pesticide use and the increasing problems of herbicide resistance, pesticides are one of the most important tools available to farmers to protect their valuable crops against weed, disease, and insect damage.

My grandfather established his fruit farm in the early 1920’s. As early as 1948 I was old enough to steer the tractor down the tree rows while he operated the sprayer. This was the days of DDT, Lead Arsenate and Lime Sulphur. My grand father thought of these product as miracles, he had never before had fruit that had so few worms and so little scab. Since then I have graduated from university and worked in crop protection industry. There is a lesson here, the products we have at present may not be perfect but they are the best we have with current technology.