The decentralization of agriculture has separated most of us Canadians from primary food production. Normally, this is fine. Farmers care about their farms and product quality, Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) have well-established safety regulations, and law enforcement bureaus actively monitor food systems for violations. Now, combine that team with the responsible labelling, consumer information, and product representation that should already be occurring if the manufacturer is credible, and Canada’s food supply is safe. Unfortunately, Canada’s import reliance and global supply chain uncertainties accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic have revealed cracks in our food supply chain, leaving far too much room for malicious intervention.

Food Fraud Realities in Canada

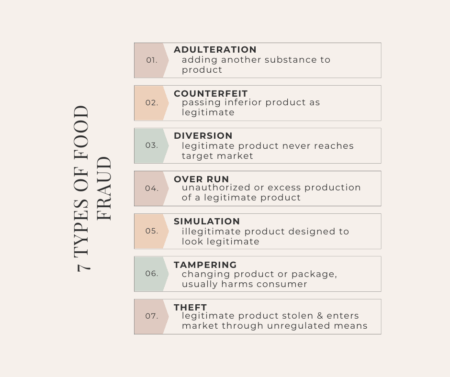

Food fraud describes the deliberate misrepresentation of a food product, such that the contents do not match the label. Fraud can come in many forms depending on the product (from diluting the product to adding ingredients to putting a completely different item on the shelf in the same packaging) and may have negative health and safety implications that are done for economic gain. This can be easily confused with food threats, which are also deliberate misrepresentations of foods but are done to strike consumer fear, harm, and supply chain disruption. Very simple examples of fraud would be selling water buffalo as bison meat, preying on consumers’ ignorance of the cost and quality difference, or as seen in the United Kingdom in 2013, when up to a third of Tesco frozen beef products were contaminated with horse meat.

Between 2021 and 2022, Canadian food fraud was generally on the decline, an optimistic statistic for a government that had finalized its five-year food policy only two years earlier, which included over $24 million directed at combatting food fraud and new inspection fees and food safety licence restrictions for exporters and trans-provincial distributors. Regardless, the same supply chain cracks emerge, and the same foods are repeatedly targeted. In 2020, CFIA reported only 87% of honey samples were authentic and free from added sugars; by 2023, leaders in the industry were calling out that there was a one-in-four chance of buying adulterated honey.

The aquaculture industry is a particularly weak point of food safety. An investigation of high-risk Canadian seafood species available at market found that, in the three years of sampling, 47% of products were mislabelled and, of those mislabelled samples, nearly three-quarters were being sold as a more expensive product. I’ve written in the past about how this continued problem is a byproduct of abandoning the 2019 boat-to-plate traceability proposal, as it is much easier to contaminate the food supply chain (or unknowingly distribute contaminated product) when participants are only asked from whom they received the product and where it will be moved next. The traceability requirement expands to all food sectors, as most food players (80%) have an inadequate understanding of available and applicable preventative food risk practices.

Policy-Trust Dynamics

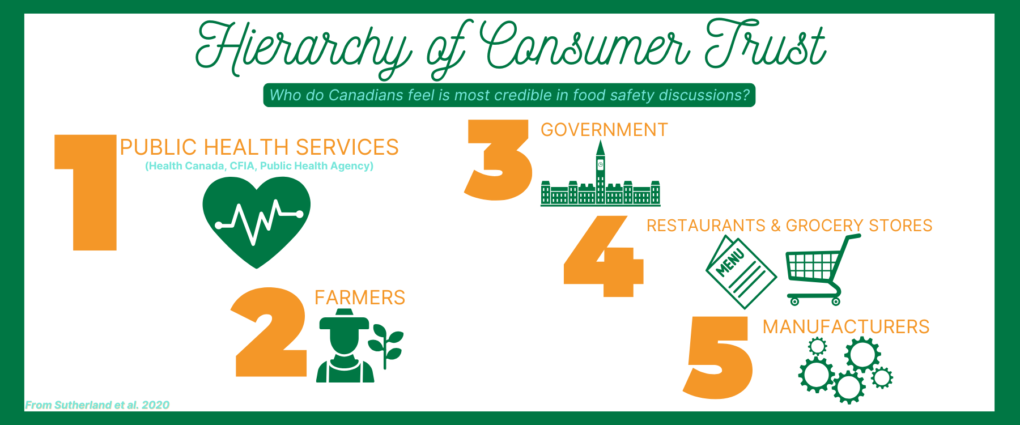

Improving food safety policy requires consumer trust to effectively work, which can be challenging to find consensus when values and personal responsibility differ across individuals and market participants. Take Figure 2, which lists the order of consumer trust of entities participating in the food supply chain.

Public health institutions who perform risk assessments, identifying the likelihood and severity of safety concerns if not properly mitigated, are understandably very credible voices. Similar sentiments are made about farmers in charge of food production, who consumers believe are unlikely to engage in operations that put public health/safety at risk. In line with the figure, it is recommended that consumers purchase from big-name grocery stores or from-source products, as branded stores likely have a better understanding of their supply chain and there are fewer stops from farm to household with from-source.

Unfortunately, perceived trust does not reduce the risk of fraud, and food definitions within regulations are typically deemed “too generic” and therefore easy targets for fraudsters. Restaurants, for example, have a much higher rate of food fraud (mislabelled food) than other sources because they have limited control over where and how their delivered ingredients are sourced. As well, distributors, the step in the supply chain before restaurants and grocery stores, believe they have less responsibility in ensuring product quality than farmers and manufacturers. When actors feel as though the problem is separate from their business and lack of mitigative action, it prevents adequate and increased surveillance, testing, and blockchain traceability that is required for improved food credibility.

The Cost of Doing the Right Thing

A few of the primary reasons for not employing preventative measures are (in no order) lack of knowledge, inability to see how their business can improve, time required, and the cost of implementation. Unfortunately, all of these are required, and it will become increasingly costlier to comply with appropriate legislation. In March 2023, the CFIA increased its food safety inspection fees by nearly three and a half percent and, again, nearly doubled that rate in March 2024. The philosophy behind inspection fee increases is that it disincentivizes food fraud by increasing individual investment in accuracy; it costs more to certify the product, so there should be a higher probability of authenticity since there is more to lose if they fail inspection.

Costs will rise further if and when government bodies recognise the suggestions made by the industry like more thorough supplier details in import documents, stronger consequences for fraudsters, and improving standards for what can and should be on a food label. Compliance is a separate problem, especially since large companies moving large quantities of products – those that are likely more financially capable of adopting fraud prevention – are better able to conceal quality changes. This is not to imply that enterprises are, indeed, misleading their patrons, rather more effort is required for sufficient monitoring, and it is easy for malformations to be missed.

Canada’s food supply is safe but there is room for improvement. It is not just a supplier problem as much as it may feel that way; we, as consumers, also have a duty to consume responsibly. Made-in-Canada products are generally a good way in which the risk of inauthentic food can be reduced, however, it completely depends on the product, available substitutes, and associated businesses. Although food fraud may not be an everyday occurrence, it is important to understand how our public health authorities protect Canada’s food supply and how the response to the issue is evolving.