Agriculture Myth Busting

Food is nothing without pollinators and, in Canada, bees are of particular importance. A third of all Canadian food is produced with the help of bees and some commodities (i.e. produce, nuts, seeds) are more reliant than others. Companies have thrived providing farmers with firsthand experience of pollinator benefits and subsequent apiculture training through hive rentals, ultimately building farm capacity for full-time bee colony involvement. Some businesses, in an effort to maintain honey quality and bee health, will rent hives for a limited list of crops and only for the (typical month-long) growing season before retaking possession – a common practice in some sectors known as migratory beekeeping. The California almond industry, for example, employs up to 80 billion bees for the two-week bloom period, emphasizing the incomparable worth of bees, which is valued at twenty times that of the honey produced by some species.In 2021, Canadian canola seed production generated approximately twelve billion dollars for the industry, of which, seven billion dollars could be directly attributed to the pollination work of bees. This figure does stand on the higher end of value estimates, but both the contribution and management costs of hives is dictated by the type of crops included in estimates. Independent of their value, bee populations have been variable across the last two decades, bringing up questions about the role of agriculture in exacerbating stressors and directly contributing to large drops in population. Whether or not agriculture is responsible for bee deaths, it is important to understand where these accusations are coming from and how much validity they hold.

Food is nothing without pollinators and, in Canada, bees are of particular importance. A third of all Canadian food is produced with the help of bees and some commodities (i.e. produce, nuts, seeds) are more reliant than others. Companies have thrived providing farmers with firsthand experience of pollinator benefits and subsequent apiculture training through hive rentals, ultimately building farm capacity for full-time bee colony involvement. Some businesses, in an effort to maintain honey quality and bee health, will rent hives for a limited list of crops and only for the (typical month-long) growing season before retaking possession – a common practice in some sectors known as migratory beekeeping. The California almond industry, for example, employs up to 80 billion bees for the two-week bloom period, emphasizing the incomparable worth of bees, which is valued at twenty times that of the honey produced by some species.In 2021, Canadian canola seed production generated approximately twelve billion dollars for the industry, of which, seven billion dollars could be directly attributed to the pollination work of bees. This figure does stand on the higher end of value estimates, but both the contribution and management costs of hives is dictated by the type of crops included in estimates. Independent of their value, bee populations have been variable across the last two decades, bringing up questions about the role of agriculture in exacerbating stressors and directly contributing to large drops in population. Whether or not agriculture is responsible for bee deaths, it is important to understand where these accusations are coming from and how much validity they hold.The Neonicotinoid Obsession

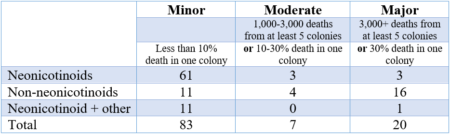

The conversation moving toward neonicotinoids seemed inevitable. The chemical group represents approximately a quarter of insecticides currently commercially available and is designed to selectively bind to and interrupt neuro-receptors in targeted pests. Neonicotinoids are frequently cited in media reports as the cause of bee mortality, except making that claim is difficult to back up. Neonicotinoids are not completely blameless, however, their inclusion in the discussion is attributable to their supposed full responsibility in past and present apiculturist mentions of the risk of “pesticides” to bee health (Table 1), despite 67% of pesticides used in Canada possessing a negligible risk to bees. Bee-pesticide incidents overall affect less than two percent of Canadian colonies although, notably, neonicotinoids affect more colonies than non-neonicotinoids. Overwhelming concern has led to increased guidelines for neonicotinoid use, including decreasing the number of applications allowed per season, decreasing the rates of applications, changing the list of allowable crops, and increasing buffer zones between treated and untreated rows.

Hive Stressors Shortlist

Concluding Remarks