One of the major themes of 2023 was undoubtedly Canadians’ fight against inflation. From altered spending habits to supply shortages as a result of indirectly linked global challenges, the grocery store was an excellent place to see the impacts of compressed wallets and the arguable over-prioritization of economics in policy. In May 2023, as consumers paid inflated grocery costs some of the loudest stories revolved around grocery store profits, grocery competition, and the long-awaited finale to Canada’s bread-fixing scandal. An inside whistleblower provided evidence of price collusion, which did not set off price-policies. This is not the only time Canadian manufacturers have skirted regulatory and anti-competition investigations. To better understand what is fair and unfair in the pricing landscape, this blog is dedicated to exploring Canada’s very real competition problem.

Confusion over Anticompetition

The issue with price-fixing is that many common retail practices can be mistaken for anticompetitive practices. Determining the price at which a product is to be sold should be an independent venture wherein market conditions and the cost of production are used to determine the profitable price point. Therefore, an individual firm is not necessarily anticompetitive, but the involvement of another firm in the pricing discussion could change that. There are many ways in which a firm may be intentionally deceptive but one common way is with price-fixing: two or more competing companies combining forces to set prices.

The price of any good is expected to represent the current state of the market, signaling the quantity that must be sold in order to clear the market and avoid surpluses/shortages. Fundamentally, price-fixing is designed to artificially move the economy away from equilibrium and, essentially, away from competition. In participating, firms have greater control over consumer movement because their behaviour can be predicted; this is the responsive nature of supply and demand.

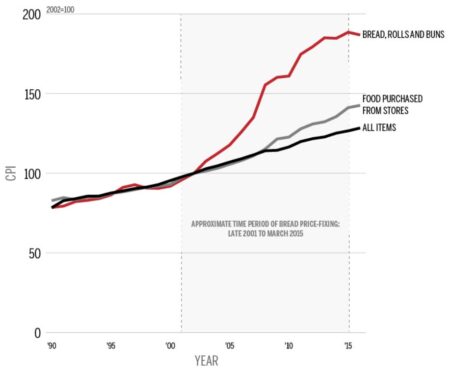

Appearing to do better or worse in the marketplace than is reality changes resource distributions, either exacerbating the disequilibrium with inefficient allocation or triggering similar pitfalls in adjacent markets. When the price increase occurs in staple goods like bread, where there is no substitute, consumers are obligated to pay the set price or else go without bread. In the case of the bread price-fixing scandal, where exactly this happened in 2007 and 2011 (Figure 1), income was inefficiently spent on groceries in times of high inflation and increasing living expenses.

Consumers can be even more confused by the trustworthiness of companies when seemingly reliable voices make loud mistakes. The NDP opposition has called for a ‘price-gouging’ investigation after Loblaw announced reducing its 50% discount for food nearing its best before date to the industry-standard of 30% highlighting a lack of understanding that muddies the water. Price-fixing in and of itself does not cause inflation. For instance, if you price-match your Sobeys flier at No Frills, this is not price-fixing. Co-op Gas Bar changing its prices in response to Husky lowering theirs is not price-fixing. The use of supply management as an industry risk management strategy is not price-fixing. Anecdotally-produced claims of ‘record grocery CEO salaries’ is not price-fixing. Although anticompetitive behaviours may be present throughout the firm, these examples are reactive business practices and not evidence of collusion or an effort to reduce the amount of competition in the given industry.

The New 2023 Competition Bureau

Canada’s bread-fixing scandal was by no means the first instance of anticompetitive action in Canada. In 2013, Hershey Canada was fined $4 million in response to chocolate price-fixing and bid-rigging six years earlier. In 2023, seven salmon farmers paid out more than $5 million for a global price-fixing scheme that negatively affected processing and distribution sites buying salmon in bulk. Again in 2023, meat companies such as Maple Leaf could be linked to a 2007 email colluding about Quebec meat prices. While the length of time between price manipulation and the time of being fined seems discouragingly long, the quality of scrutiny and the basic existence of a fine is proof of the Competition Bureau, despite increasing calls to improve monitoring mechanisms.

Indeed, the impact of price-fixing affects less than one percent of consumer expenses therefore, consumers are unlikely to truly notice when price-fixing occurs. In many instances, for the Competition Bureau to launch an investigation into anticompetitive practices, an informant may be required, although those individuals are hard to come by. In response to increased investigative calls into Canadian grocery retailers, the Competition Bureau and the Competition Act underwent strong reform. To prevent future instances of anticompetition, the Competition Bureau removed fine limits, meaning offending companies may experience higher settlement values and/or stricter jail sentences depending on the perceived economic harm caused to consumers. It may be also worth mentioning that price-fixing is a criminal offense; with that title comes criminal consequences and, as a result, the inability for firms to skirt punishment by offering charitable donations instead.

What is ‘Fair’ in Canada?

It can be said that the Canadian government wants as level a playing field as possible until a firm starts excelling, then they would prefer to cripple that company for the sake of the playing field. That is not fair competition, however, it is a sign of Canada’s complacency. In a 2023 interview, Dr. Charlebois points out that blackout periods – the November through January term where grocery stores freeze price changes for “holiday altruism” – can be considered one of the most obvious examples of price collusion and yet, the government appears disinterested. Since the turn of the century, general retail competition has diminished, leading to increased comfort of the top-performing companies and less incentive for firms to reduce prices.

Determining whether a firm is anti-competitive or participating in savvy business practices is difficult to determine because the optics of the situation can change the conclusion. To clarify, while claiming price-fixing occurred to remain competitive will never be an accepted defense, proving a firm engaged in anticompetitive behaviour is an extremely difficult task. It is here that consumers hold the greatest power in combating price-fixing, beyond what is capable of institutions that are likely more removed from the day-to-day grocery markets. Increased monitoring may decrease anticompetitive participation, however, the increasing economic policy landscape may warrant the greater involvement of economists, who may be able to easily spot collusion, cartels, and market noncompliance more than investigators. Further, growing Canada’s network of independent grocers, which simultaneously improves local accessibility and competition, may be one of the strongest tools available for encouraging genuine grocery competition. Regardless of the how, it is valuable that government continue amending Canada’s competition framework, in order to maintain investment and improve market statistics. Without true fairness in firm competition, consumers, much like professional adversaries, will be harmed by the lack of action.