The regulatory oversight typical of Canadian fish production is designed to maintain safety and promote quality uniformity among foods. Seafood is no exception and yet, the industry states that the government has effectively stifled rather than aided fishers’ success. Changing standards combined with confusion over where the shared jurisdiction of federal and provincial entities starts or ends can limit the confidence and security of those involved in the sector. This has led to concerns as to whether Canada is truly committed to reconciliation, if the government cares about its fish producers, or if coastal communities can survive without intervention. Ultimately this calls into question the efficacy of national programs. For the sustainability of Canada’s multi-billion dollar seafood industry, it is vital to understand the regulatory landscape as a precursor to assessing expansion opportunities.

Coast-to-Coast Aquaculture

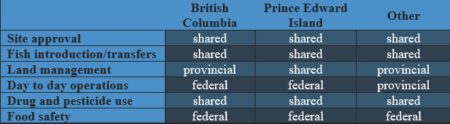

All Canadian fishers must follow the Nationally defined regulations to ensure uniform quality amongst products destined for the market. The biggest of these frameworks is the Fisheries Act, which focuses on sustainable management, including licensing and animal welfare protection, among more specifically funded projects. The act is typically applicable to the saltwater surrounding our country and is designed to guide production, whereas provincial standards take on more of an enforcement role, and generally apply to more local freshwater fish environments. It is often the combination of program complexity and implementation costs that impact how efficient a given policy is but evolving changes to innovation and performance baselines have muddied the water, leading to calls for improved provincial competence, especially in instances where provincial and federal standards seemingly approach different goals. Given the differences in legislation depending on the province – BC, PEI, and other provinces (Table 1) – it can be difficult for regulators to know where they are allowed to make improvements to the system, leading to the trend of outdated and inaccurate resources being used for policy decisions.

Naturally, hearing “fish” leads Canadians to think of two locations: British Columbia and the Maritimes. Not surprising, as aquaculture is one of three of British Columbia’s most vital industries and, thanks to trade with China, Nova Scotia has seen a 168% increase in the value of their shellfish since 2012. This value improvement, however, may be more indicative of the seafood trend that mirrors that for agriculture: a decreasing number of license-holders and vessels in the waters, while the value of the license has increased. Similarly, while the majority of trade value is in shellfish, Canadian aquaculture is primarily finfish like salmon and herring, leaving swaths of the interior to develop their own slice of the industry.

Saskatchewan and Manitoba, for instance, have very few fish farms for human consumption, preferring instead to use aquaculture for feed uses (i.e. fish meal) or recreational sites. The trouble with inland facilities is the inflated costs of stricter regulation and tank filtration technology dependence, which limits how profitable prairie aquaculture could be. Regardless of use, facilities must still abide by applicable Fisheries Act legislation, and therefore, must still pass their license application and site inspection before fish can be welcomed on site.

Market Ebbs and Flows

The success observed in the Atlantic is not as widespread as reputation would have you believe. Since 1990, the value of Pacific salmon has declined by well over $200 million, largely due to the combined overreliance on salmon and declining stocks. Mackerel, as well, is seeing large drops in stocks due to seal predation, leading to a misguided moratorium that is unlikely to improve populations the way legislation hopes. (This directly relates to the importance of fishing in the Discovery Islands, but that discussion is saved for the next blog in this series.) While lobster in the Atlantic has not faced the same market threats, opportunities do exist for Canada to improve its resilience to seafood threats. Given that the industry is still economically recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic and that 2023 marked the completion of many Department of Fisheries and Oceans programs, now may be an excellent time to re-evaluate industry gaps.

One major gap in the Canadian economy is the lack of value-added products, leading to consumption reliance on international production and increased investment in, for example, Norwegian cod companies. Canada’s crab industry is particularly ready for evolution, as calls for functional processing plants are considered by harvesters an excellent step towards improved market value and community health. “Towards” is the keyword in that sentence, as fishers are still largely unsatisfied with market standing when Canada lacks value-added options. In April 2024, crab harvesters reached a new deal to speed up market movement by introducing a price floor and end-of-season settlement if global prices exceed the floor. This is one example of the government listening to the concerns of fishers, although arguments can be made that such is few and far between from an institution that tends to take their time when addressing the industry.

Take, as an extreme, the 2020 lobster license registration stall in Nova Scotia that led to the arrests of dozens of Indigenous harvesters. Courts cited a lack of consistency with the Marshall Decisions (1999), which was the hallmark Supreme Court case allowing Indigenous (non-commercial) harvest for themselves and their Nation, whereas the Department of Fisheries and Oceans saw their legislation appropriately enforced. The Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation on the West Coast, whose community and economy heavily rely on fish farming, also highlights the necessity of aquaculture for the social welfare component of the industry that the government chooses to overlook in favour of environmental exaggeration. Therefore, there is an opportunity for the government to take a more supportive role as opposed to one of enforcement, as it would also better recognise the locality and social dependence of fishing communities.

Blue Economy Framing

Yes, for Canada’s resource-based seafood economy, environmental tradeoffs, both natural and directly related to aquaculture, are ever-present and vital for industry longevity. Canada is increasingly devoted to creating a “blue economy,” a broad term that describes the environmental, social, international, and innovative resiliency goals for global oceans. And it appears that Canadians are open to this approach, as 40% are willing to pay a slightly inflated price for seafood if the sustainability of the product can be guaranteed.

The Marine Stewardship Council label, which often appears as a small blue fish checkmark on packaging and menus, is a globally recognized wild-caught sustainability program fishers can opt into. However, the 2023 update to improve certification with changing sustainability standards, made certification requirements overly broad and ‘unworkable,’ ultimately creating confusion amongst producers as new standards will not be mandatory for another few years. The main concern is over the commitment to reducing ghost gear – a noble cause but an untraceable reality of fishing. To clarify, ghost gear refers to equipment that has been lost or abandoned in the ocean, and can cause major ecosystem damage. Much like how difficult it is to determine who threw their granola bar wrapper into the wind, it is incredibly difficult to trace loose gear to the appropriate vessel, leading to increased government and private investment efforts to recover equipment.

An overreliance on misinformed activism has injected conservation policy into numerous aspects of Canadian production. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as sustainability will continue to shift and adapt to global realities, both physical and administrative. However, it can become an issue when forecasting is stifled by environmental priority. Take, for instance, BC salmon farming which, in 2017, was forecasted to triple gross domestic product (GDP) based on its (sustainable) performance at the time; two years later, industry success began dropping in response to increased policy involvement. This is just one example of the government opting for misguided environmental zeal at the expense of social sustainability. By protecting fishers’ livelihoods, they are allotted numerous stabilities like income security, better insulation from market shocks, and improved labour quality. Transparency or traceability programs, like the abandoned boat-to-plate commitment made in 2019, would simultaneously contribute to social protection and updating sustainability baselines.

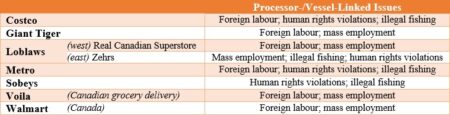

Traceability is particularly important for Canada, given our reliance on global fish markets and the multitude of (deliberate and accidental) ways lesser quality seafood products make it onto our plates. The seafood we eat at home comes from a heavily integrated production system, and therefore most of our fish suffer from the same ethical dilemmas such as the mass employment of minorities and forced foreign workers (Table 2). This blog will not go into depth about these violations but I encourage you to follow the source link to read more detail about labour and human rights injustices in the global seafood sector.

The labour violations appear of particular concern to Canada, which is in the process of implementing a new accountability framework: Forced Labour and Supply Chain Reporting Law. Unfortunately, critics of the published proposition have called the effort nothing more than a “checklist” unable to truly enforce the accountability that is needed for the sector. If traceability can be improved, it is possible that the imports that do not meet social protection requirements can be stopped before reaching grocery shelves.

Concluding Remarks

There are ample opportunities for Canadian aquaculture to expand and meet the standards required by market participants and end-product users. While some challenges can be overcome by domestic policies such as securing fishers’ livelihoods, international market forces may be harder to accommodate. Canadian fish production can be resilient if institutional programs can efficiently target areas in need of support, but determining where those targets are will require that fishers’ voices are heard above the misinformed. Keeping aquaculture and its policies science-based is the best way for Canada to remain an adaptive and sustainable fish provider.