The broadness of the term ‘sustainability’ implies a multitude of approaches. The same is true in agriculture, as farmers’ drive to be environmentally conscious, economically successful, and personally gratified means there is no one-practice-fits-all method to solve each farm’s individual and unique hurdles. For example, integrated crop-livestock systems (ICLS) – managing crops and animals on the same land base – can only ever be considered an opportunity for farmers to improve on-farm climate resiliency if infrastructure is in place to accommodate both production streams.

With that in mind, my master’s research took ICLS a step further, assessing its feasibility in the prairies when cover crops, specifically, are used to graze beef steers – neither of which are conditions of ICLS, just conditions of this particular research question. An additional complication came when we also introduced a social aspect, designed to alleviate some learning curve risks (or the simple truth that starting a new production method will not be mistake-free the first few years it is attempted). This new aspect: a partnership between a primarily beef and a primarily crop producer under the assumption that each farmer would be comforted by only having to focus on a single enterprise, rather than both. While this blog can’t make any definitive conclusions as to whether ICLS will become part of mainstream Canadian agriculture (which will be discussed in a few paragraphs), that does not mean the results are barren.

Integrated Systems in Practice

Integrated crop-livestock systems are based on the principles of regenerative agriculture, a term which refers to practices that recognize the scarcity of natural resources like land, water, and biodiversity. It’s important to look at these types of opportunities holistically, as “explorable and exploitable” opportunities to improve production efficiency may not be directly recognizable in the marketplace. Ma et al. (2017) note that growth is contingent on effective management of all of capital, resource use, and production efficiency; a change in any of the factors therein may impact farm sustainability. Often, resources and capital investment push against each other when considering the scarcity characteristic of agriculture, contributing to the adoption hesitation for ICLS.

By complementing natural ecology (in the case of ICLS: cover crops, cattle, soil microbes) and farm limitations, long term physical resiliency is optimized. That is the point of ICLS, after all: farm sustainability and not resource substitution. However, if ICLS adoption is based on perceived fit according to farm(er) skills, and the ability of ICLS to meet those needs is individualistic, then perhaps ICLS, on an ecological standpoint alone, is not incentive enough for widespread use in the prairies.

The Socioeconomic Angle

The seemingly ever-present condition of a cattle rancher who already grows their own feed adopting ICLS has left both a gap (from insufficient recording and performance diversity) and a bias (from short term ICLS use) in surrounding literature. As a result, there are many unanswered questions like how social a venture can ICLS be? or how does ICLS compare to conventional prairie methods? – both of which motivated my research.

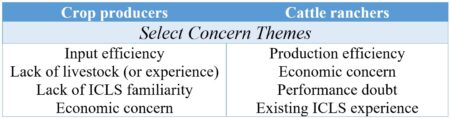

The answer to the first question is: it’s still largely subjective. While some may find working with a nearby farmer to fill production needs advantageous, our results display that such is not universal. Survey participants were able to voice factors that determined whether or not they would accept the ICLS partnership scenario randomly presented to them (Table 1), and those yielded no clear pattern. However, despite performance or economic guarantees, the majority of farmers were uncertain of accepting the scenario to which they were presented, with feelings of lost decision-making power and lack of ICLS comfort overall, contributing to various answers throughout the survey.

Table 1. Common themes present in respondents’ ICLS partnership decision making

Answering the ICLS performance question is slightly more difficult due to the expected unpredictability of the Canadian prairies. The values used in ICLS scenarios were (calculated) based on various fields… or rather, field. The project lead, Dr. Bainard, explains in this interview with the Western Producer how, due to unforeseen natural circumstances such as koschia infestations, the number of fields on which the economic estimates are based was reduced from four trials to one from the Swift Current Research Centre. But that also emphasizes the individualistic success of ICLS, and the risk one takes when adopting it.

For instance, the cover crop mixtures used in the field trials were comprised on forages without market value. Therefore, the advantages of all the growing costs are only observed in the long term soil benefits or the market outcome of beef cattle (based on what nutrition needs are met by which cover crops). Although the costs of heavier polycultures (i.e. more variety of species) are greater than conventional costs, it appears as though the long-term input substitutability such as the lack of chemicals required indirectly compensate for the limited economic differences, as is consistent with literature. The economic performance of ICLS, and the lack of mainstream awareness of that performance, appears to be where the majority of the hesitation exists for farmers. This implies the need for incentivization, although likely not with a partnership compensated by an external party, as suggested in my research.

“No” is Still an Answer

There is so much diversity in production priorities across the Canadian prairies that ICLS cannot be the be-all-end-all sustainability solution. While yes, ecological performance is worth a second glance, those results come from sustained use with mostly ideal conditions. Sometimes, that is an unrealistic request in agriculture, where markets are constantly changing and climatic conditions are predictability worsening. There is such range in opinions and in production considerations that the attributes featured in the partnership experiment do not sufficiently cover respondents’ ICLS anxieties. It would be ignorant to start promoting ICLS as a sustainability solution to everyone.

Therefore, incentivizing ICLS adoption, even without the partnership mechanism, would not be worth the investment, as the system seemingly requires pre-established infrastructure and production mechanisms that are not universal across prairie farms. This is not an inherently negative statement since it speaks to the agricultural diversity across Canada, but it should accentuate an opportunity to explore even more ways to meet the evolving requirements of agricultural sustainability.