By Kolby Haynes

University of Saskatchewan student

What is livestock transportation? Livestock transportation is when livestock gets transferred from one place to another. This can be done by air, road, ship, or rail. There are tons of reasons to transport livestock: slaughter, new homes, changing pastures, taking them out to pasture, breeding, livestock shows, and so much more.

To give background, my family runs a purebred and commercial cattle operation. We don’t transport many animals to pasture, but we take part in cattle sales and shows all over the province, so we are always on the road. After talking to many people at shows, I realized injuries while travelling are common. The transportation of animals is very important to the agriculture sector. When buying animals, you don’t want to receive one that is lame or injured, so shippers must know the regulations associated with livestock transportation.

CFIA

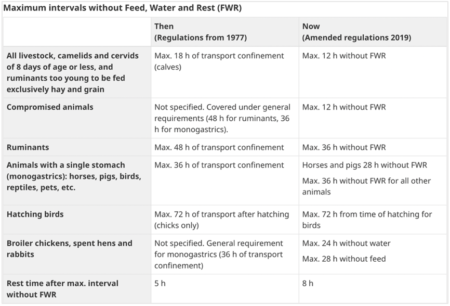

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) updated transportation regulations in 2019, these new regulations can be found in Figure 1. To protect both the animals and the transporters, these new standards enhance the welfare of animals during transportation. In addition to bolstering Canada’s trade standing, ensuring the animals arrive safely will boost customer trust that they are purchasing high-quality goods). More driver training and shortened travel hours are how this is implemented to make sure the animals can survive lengthy travels or stays. Producers and transporters must disclose when the animals last had a meal, a drink, and a chance to relax. This reduces some of the stressors associated with transportation.

There are a few things that drivers need to be mindful of when carrying animals. In severe weather, the CFIA ensures that it is required by law that drivers make sure no animals are harmed or experience pain during loading, transporting, or unloading. It is not solely the responsibility of the transporters; the owners, producers, and receivers must also make sure they can adequately prepare the facilities and animals to prevent any mishaps. Steer clear of loading during the hottest parts of the day, load up smaller numbers, park in shady spots, and install hole covers in the winter to protect against extremely cold temperatures. The CFIA’s top priority while moving livestock is their safety, so they have laws in place to maximize that safety.

Fit for transport

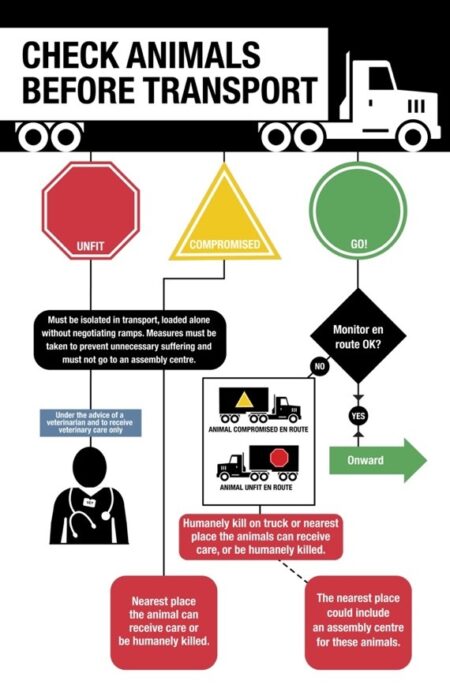

To lower the risk of harm, things like anti-slip flooring are quite helpful while transporting livestock. There are a lot of steep hills, gravel, shrubs, and limited water in the area where I live. Our cows on pasture often sustain a few injuries from this each year. As producers, we are forced to hold these animals until they are well enough to travel since their injuries render them less suitable for breeding and transport. We have two viable options: either we butcher them, or we kill them humanely on our farm. We therefore use caution when delivering them to the abattoir because they should not be transported in large groups. They get their compartment in the trailer and are handled very carefully to achieve this. In Figure 2 there is a flowchart that truckers and transporters can follow to ensure that an animal is fit for transport and steps to take if they are not fit.

Making sure the animal can be moved is the most crucial factor to consider while transporting it. A fit animal will exhibit visible flaws such as lameness, sickness, droopy ears, runny nose, severe thinness or skinniness, open wounds, and other defects or injuries. Animals in this group are considered compromised. Animals that are compromised must be transported either alone or in a separate trailer compartment. The compromised animal’s stress can be reduced by loading last and unloading first. The solution is to keep the trailer from being overpacked. Having a trailer like the one below contains many compartments making it easier to separate injured animals to their own area.

There are a few actions people take regarding weakened animals that are not suitable for travel as producers. Making an on-farm call with the veterinarian is one step you can take if you want to take this animal to the clinic. This allows the veterinarian to visit your farm and treat the animals, which reduces stress for the animals as they do not need to travel. But occasionally, things don’t turn out like that. Hauling may still be necessary even if an animal is not the best candidate for transportation. Sometimes, injured pasture animals who are hardly able to walk need to be sent to the farm or veterinary clinic for care. As a producer, we aim to minimize the animal’s suffering throughout the transportation of these unsuited animals. Straw, wood shavings, and woodchips can be used to provide the animals in the trailer with additional cushioning. Giving each animal a space in the trailer also makes it less congested, which lowers the possibility of additional injuries and stress. Frequently, these injured and sick animals are the first or last to enter or exit the trailer, giving them the extra time, they require to move. It helps to ease the suffering of sick or injured animals if a veterinarian is available to treat them on the farm. Safe transportation requirements are not well known, and it has been brought to my attention that this could be a significant problem down the road. Without proper measures, serious injuries can occur, and animals can be greatly injured by unsafe loads or even killed. Today, more animals are being sold and moved because of the current high price. People tend to take fewer precautions when livestock hauling is in higher demand. Trying to fit a few extra animals on a trailer seems like a worse idea than investing more money in a new truck. For motorists, other road users, and animals, a fully loaded trailer poses a serious risk. A few summers ago, I saw some piglets fall out of an overloaded trailer while I was travelling down the highway. After learning that some pigs were saved and others lost their lives, I’ve come to understand how crucial transportation laws and regulations are. Taking some extra time to ensure the animals are loaded correctly and not overcrowded can eliminate many potential risks.

Biography

My name is Kolby Haynes, I am 20 years old taking my Agriculture Business Degree at the University of Saskatchewan. I grew up on a ranch just outside of Biggar SK where my family runs purebred and commercial Black Angus cattle. During the summers I have had the opportunity to work locally in Biggar at The Rack Petroleum, an agriculture retail company, where I enjoy interacting and serving the producers in not only my area but throughout all The Rack locations. Besides ranching and working at The Rack, I enjoy showing cattle, 4-H, playing almost any sport as well as coaching the younger-aged sports teams in my community.