Can America and Canada’s Plant Regulatory Systems Become One System?

Canada and the United States are each other’s largest trading partners. Of all the products that are exported by Canada, 75% goes to the US, while 20% of US exports come north. In spite of the increased economic integration, both countries still maintain their own regulatory systems for approving new varieties of plants. This is in spite of the fact that the varieties are often produced in both countries. The time has come for this to change.

Under the present plant variety registration system, new varieties of plants that are developed by private companies and public institutions must submit data to regulatory agencies in both Canada and the US. The data required includes the new varieties potential to cause an allergy if it is eaten by humans or animals and any possible environmental effects, as well as information on the agronomic traits of the plant such as yield increases or disease resistance. Usually, the package of data is the same in both countries submissions.

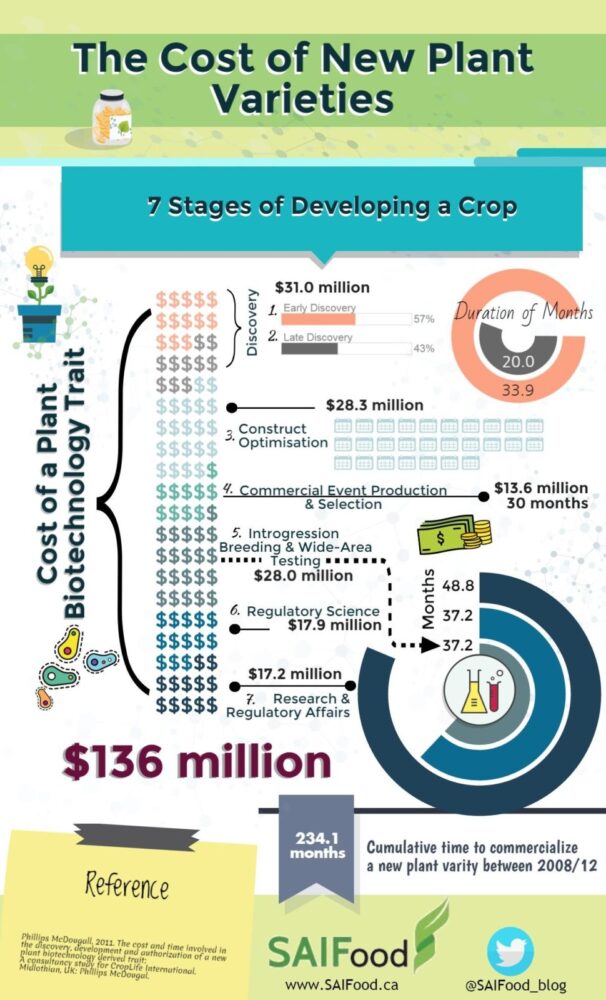

Once regulators receive the package of data it takes about two years for the regulatory agency scientists to review all of the data and to decide whether the new variety should be approved for farmers to grow. Having duplicate submission and review processes is costly for public and private breeders. Ideally, regulators in both countries would receive a single submission and could identify the best regulatory experts, then jointly reviewing the data, reaching a decision in less time than is the present case. This would benefit the variety developers in that getting variety approval would be less costly and would give farmers access to the new variety sooner. The benefit to consumers is that food prices would be lower due to the new varieties.

In theory, a shared plant variety regulatory system should be a relatively simple thing to accomplish. In reality, it is not. Both countries have science-based regulatory systems, but apply them differently. Yet the outcomes are the same, new plant varieties are approved in roughly the same amount of time. Canada’s system is slightly faster at this than the US, as it takes about 22 months to approve a new variety, compared to 30 in the US. The challenge is that each nation argues it has the best variety registration system and to accept that the other nation has aspects of their variety approval system that are superior, raises the question to politicians that if the other country’s regulations are superior, why aren’t we using them? This sovereignty battle places a considerable obstacle in the path of a single variety regulation agency for both countries.

It has recently been estimated that it costs the variety developer as much as $17 million to get regulatory approval and can take as long as 4 years. If this cost and time could be halved, then the benefits would be substantial. The additional $8 million in savings could be reinvested in developing new plant varieties that will further contribute to improving global food security rather than being spent on inefficient regulatory approvals.

Something I have long wanted to see. Not only for GMO but also same grade and safety standards for all the crops we grow.