What could climate change mean for ag?

In October I had the good fortune to participate in CQuest: Charting a Course for Climate Research in Agriculture, an event made possible by the International Life Sciences Institute’s Research Foundation as well as: Monsanto Company, Soil Health Partnership, Washington University in St. Louis, Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, Howard G. Buffett Foundation and the United States Department of Agriculture. The objective being to develop a set of prioritized research targets for a US “climate smart” agriculture. I quickly noticed how much further ahead the US is to Canada in developing research priorities addressing climate change in agriculture.

Throughout the event various sessions were held on topics ranging from soil health, livestock pasture and grazing, to pollinator health and more. The over-arching goal of these workshops was to develop a prioritized research agenda to achieve a carbon-neutral agri-food system in the US through a focus on soil carbon and soil health.

Increased Carbon Emissions

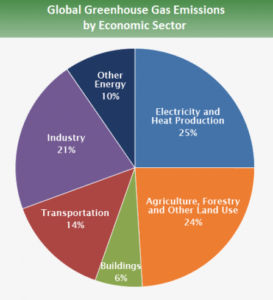

Increased carbon concentrations in the atmosphere is an issue across nations and industries, therefore achieving carbon neutrality has become a goal to work towards. One of the leading carbon emitters of is the agriculture and forestry sectors, responsible for one-quarter of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. So how do we continue to produce our foods, while maintaining profitable agriculture and reducing agriculture’s carbon footprint?

Increased carbon concentrations in the atmosphere is an issue across nations and industries, therefore achieving carbon neutrality has become a goal to work towards. One of the leading carbon emitters of is the agriculture and forestry sectors, responsible for one-quarter of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. So how do we continue to produce our foods, while maintaining profitable agriculture and reducing agriculture’s carbon footprint?

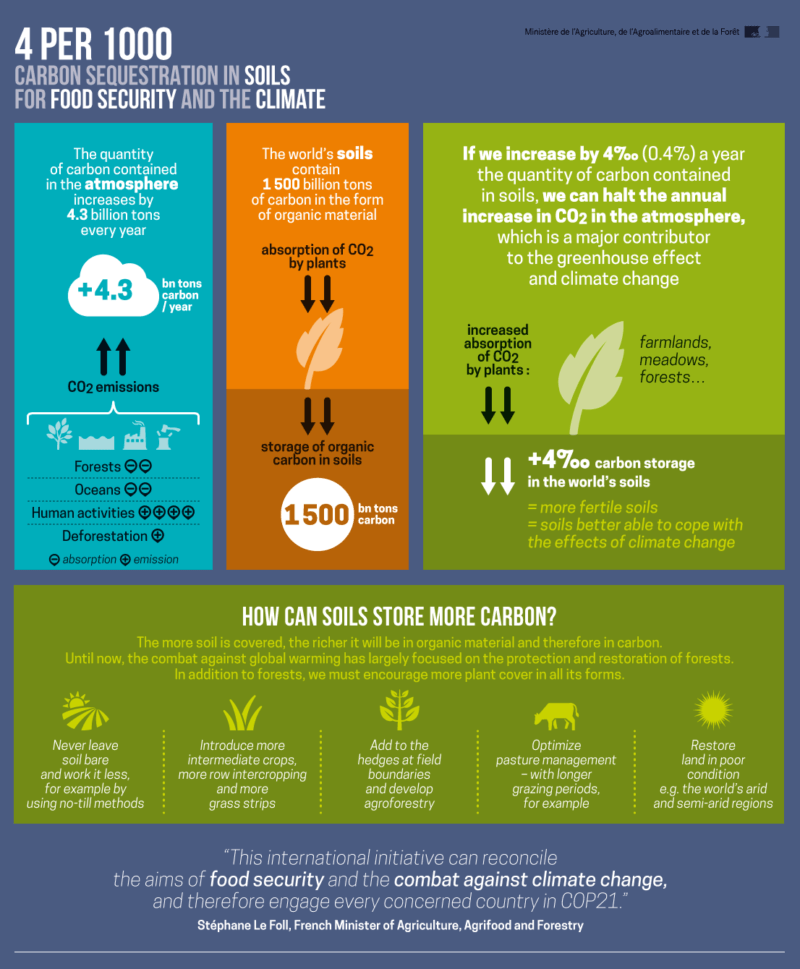

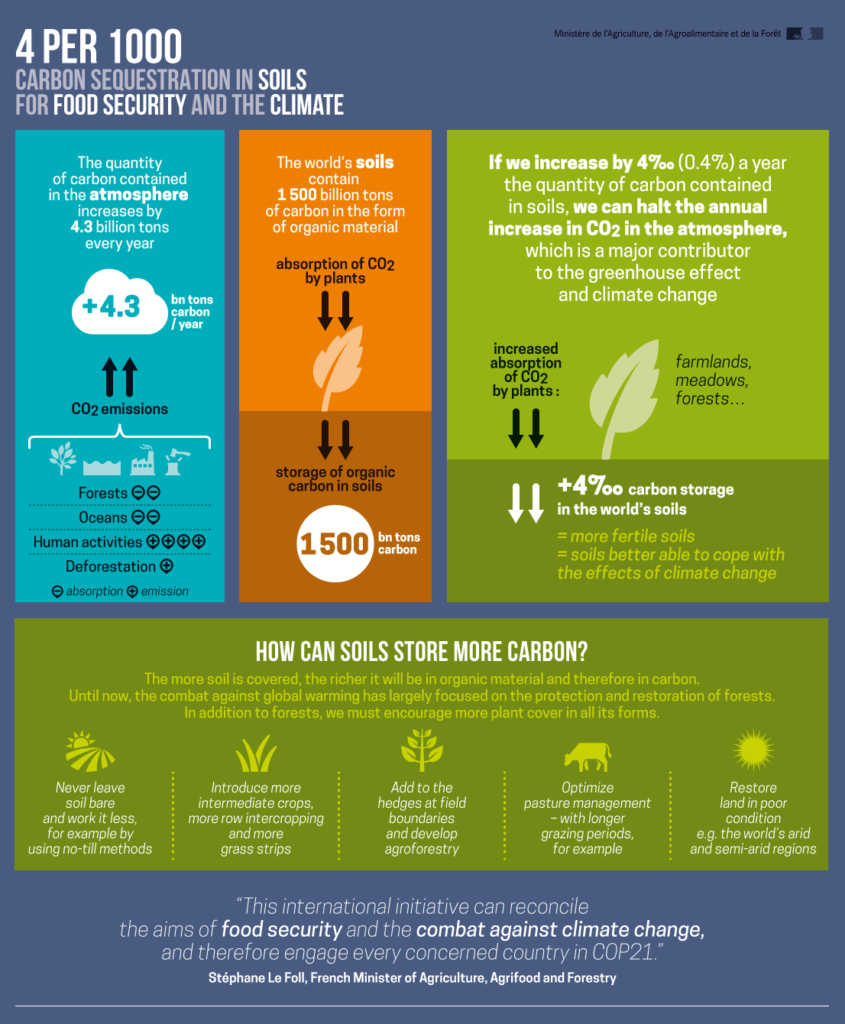

Although agriculture is a GHG emitter, it can also offer a unique opportunity for GHG emission reductions through soils ability to sequester carbon. Researchers in France have theorized that agriculture could be used to stop the rise in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. They believe the top 16 inches of soil could be the solution. If carbon stocks in the top 16 inches of soil could be increased by 4 parts per 1,000 annually, the soil could become a carbon sink that mitigates climate change. However, this is based on current deforestation practices ending. If soil sequesters carbon at an increased rate of 4 parts per 1,000, this will increase yields by an estimated 1.3% annually.

Land management practices will need to change for carbon to accumulate in the soil. Promoters of the ‘4 per 1,000’ believe that soil can accumulate carbon for 20 to 30 years following the removal of intensive tillage practices. Canada has already taken these first steps, where 70% of the land is under a no-till regime, while only 10-12% of the US have adopted this practice. Soil health in the US may also lag that of Canada as the use of cover crops for the winter isn’t a common practice in the US, while soil snow coverage in Canada contributes to soil health. (Who knew there’s a benefit to snow!!)

What would a policy of ‘4 per 1,000’ mean for Canadian agriculture?

What would a policy of ‘4 per 1,000’ mean for Canadian agriculture?

Farmers that haven’t adopted or incorporated no-till land management systems would bear the brunt of the cost, such as organic farmers. Why? Organic farmers rely more heavily on tillage to control weeds than conventional farmers. The downfall with tillage is that with each pass, carbon is released into the environment rather than being sequestered in the soil. Farmers that have incorporated herbicide-tolerant (HT) crops are capable of providing more carbon efficient weed control as they no longer rely on tillage to control weeds. The removal of tillage also increases moisture conservation and reduces soil erosion.

Canadian agriculture will and may already be affected by climate change. So far, Canadian farmers have done a great job of adopting technologies that reduce GHG emissions. However, Canadian agriculture needs to develop a research plan to fill the gaps on how the ag industry should respond to climate change.