Centres of Innovation or Bottlenecks on Knowledge Sharing?

Several reports over the past decade identify Canada as a highly innovative country[1]. However, many reports give Canada a failing grade when it comes to the commercialization of innovation technologies. The Global Innovation Index ranks Canada 16th.

Many of these reports have suggested that the transfer of knowledge (or technologies) from universities to private companies is very poor, therefore lowering the nationals innovation arena and economy. Typically universities receive public grants to undertake research, which leads to patents that can be licensed private companies. It is this technology transfer from universities to private companies that is frequently cited as a major flaw in Canada’s innovation strategy.

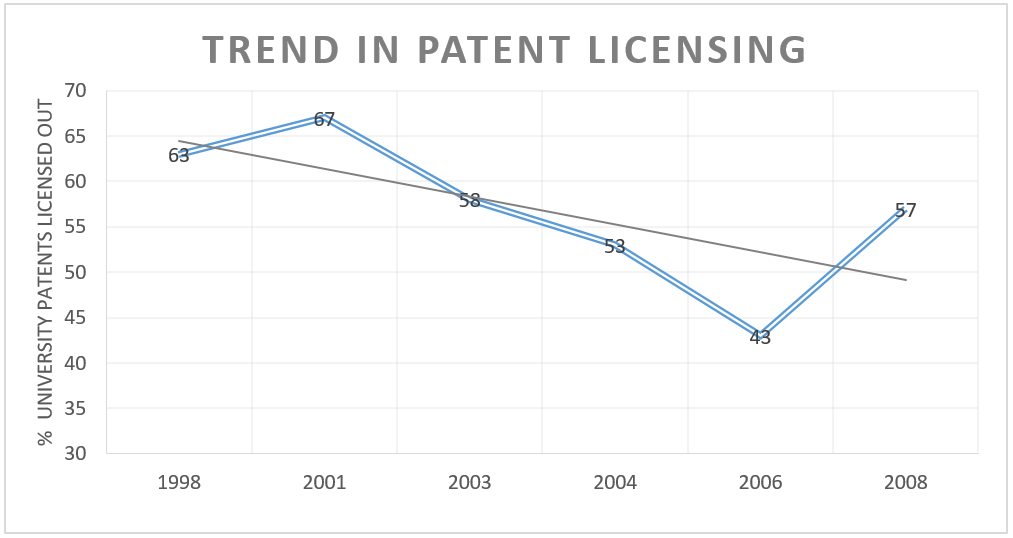

I recently analyzed university technology transfer data, finding a different perspective. In 2008[2], nearly 6,000 patents were held by Canadian universities, with 57% licensed to companies. The trend in licensing declined from 2001-2006, rebounding substantially from 2006 to 2008.

‘An assessment of Canadian university technology transfer offices’

A comparison of research outcomes between Canada, the UK and the US, Heher (2006) found that Canada had a patent filing rate of 17 per $100 million of adjusted total research expenditure (ATRE) in 2002, compared with 21 in the US and 35 in the UK. In terms of efficiency, the UK leads as their patent filing rate is achieved with US$3.1 billion in research funding, while Canada had US$2.5 billion and the US was more than tenfold above this with US$31.7 billion.

In 2008, the revenue that Canadian universities received from patent licensing amounted to $53 million. A mere $2 million greater than the cost of managing the transfer of these technologies. Expenses to manage university technology transfers are increasing more rapidly than licensing revenues. The transfer of intellectual property from universities to the private sector should never be viewed as a stream of revenue for universities. Breaking even should be the target.

Hiring additional employees to work for university technology transfer offices could help, yet this is not a sustainable solution as the cost of hiring a new staff person is greater than the revenues generated from the additional licensed technologies.

A couple of observations can be made in regards to Canadian university patents. The size of Canada’s the private sector may contribute to a lower value for university patents. With fewer firms than say the United States, there are than fewer firms willing to competitively bid to secure a university’s technology license, resulting in a lower value for the licensing agreement. A second observation is that the success of Canada’s university patent licensing is nearly 60%. Universities role in research is to construct basic proof of concept, leaving the private sector to scale the technology up and commercialize it. If a licensed technology ends up not making it to the market, that is not the fault of the university.

The commercialization of innovative research is crucial in our knowledge-based societies. Universities are doing a reasonable job of transferring patented technologies to the private sector. While this could undoubtedly be improved, Canadian universities are doing their part in Canada’s innovation system.

[1] The State of Science and Technology in Canada, or Mobilizing Science and Technology to Canada’s Advantage

[2] 2008 is the most recent year of data, as the federal government stopped collecting this data in 2010.