If you haven’t noticed vanilla is everywhere & in everything. But why?

Thank Hernan Cortes, Edmond Albius, Hugh Morgan &Thomas Jefferson for vanilla!

Vanilla originated in the New World’s Mesoamerica, now known as Mexico, and was brought to Europe along with cocoa, in the 1520s by Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes. It was used in ‘chocolatl’ a cocoa drink (masking cocoas bitterness and acidity) for societies elite. In the 17th century, apothecary Hugh Morgan, introduced vanilla (chocolate-free) confections to Queen Elizabeth I, launching vanilla’s popularity across Europe. From this, vanilla found its way into French pastries and more important into ice cream. By the 1780s Thomas Jefferson discovered vanilla ice cream while in France, and brought it back to America.

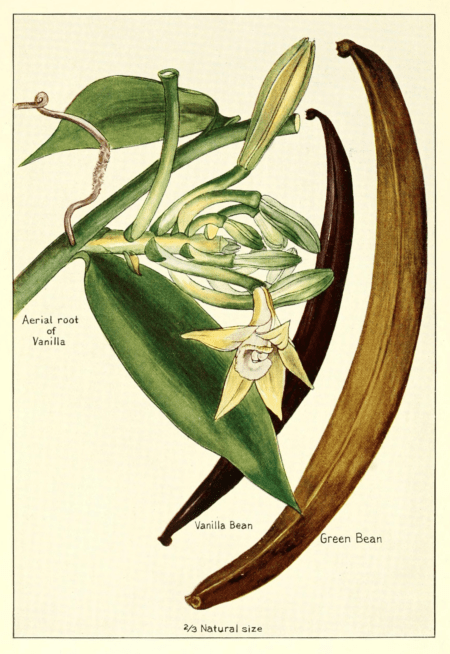

By the 1800s, vanilla was still rare as the transplanted crops had yet to successfully produce vanilla pods. It wasn’t until 1841 when Edmond Albius discovered that the orchid could be hand pollinated. After his discovery, plantations of vanilla orchids began across Madagascar, Tahiti, and Indonesia, allowing vanilla to become a staple of today’s foods and fragrances.

Naturally small

Natural vanilla production is limited. According to the FAO, in 2017 vanilla was harvested across 98,576 ha, an area equal to Berlin, Germany. Production is also timely, taking 3-5 years for the orchid to mature, with only a 24-hour window to pollinate, followed by 8-9 months for pod maturity. The harvested green pods are picked, cured and dried to develop the vanilla flavour. The curing process takes roughly “5-7 pounds of green vanilla beans…to produce one pound of processed vanilla”. As a result, the 8,144 tonnes of green vanilla pods harvested in 2017, produced between 1,500-2,000 tonnes of natural vanilla.

It’s everywhere

The average American consumes two vanilla pods a year. If it takes seven pods to produce one pound, the US alone would demand 41,000+ tonnes of vanilla. That is 5 times greater than the 2017 harvest. Obviously, demand is greater than the supply, so where is vanilla coming from? The answer is vanillin. Vanillin is one of the 250+ flavour components of cured vanilla pods, and the one most associated with natural vanilla flavour and smell. Making up 2% of the vanilla pod, vanillin is extracted for natural vanilla products. Vanillin is also produced through synthetic or artificial processes. Artificial vanillin makes up 99% of vanilla on the market.

Non-vanilla vanillin a.k.a artificial vanilla

Vanillin also can be produced from petrochemicals, clove oil (eugenol), spruce pulp (lignin), and a few less savory sources. Non-vanilla based vanilla is more affordable to source as an ingredient, as natural vanilla is the 2nd most expensive spice (behind saffron). Recently, C&EN and The Economist report prices increasing from US $25/kg to US$500-600/kg. At those prices, the food industry can’t afford to use whole vanilla pods and relies mainly on synthetic extracts. If you were to purchase 1 kg of vanilla extract from Walmart.com today, a natural extract would cost US$75, whereas its artificial equivalent extract costs only US$17kg. At that price, what would you choose?

Despite the price difference, in 2015 many food processors announced plans to eliminate artificial vanilla additives from food products (starting in the USA chocolate market). The limited production of natural vanilla and the recent vanilla shortage means its unlikely big firms will move to natural sources.

Future of Vanilla

As a lover of vanilla, I question the future of vanilla? With the push for natural flavouring over synthetic, is it possible to meet this growing demand?

Perhaps vanilla demand can be met. It’s likely there’ll be more natural vanillin production from non-vanilla source. Solvay’s Rhovanil®, a natural vanillin product made from fermented ferulic acid, is an option. However, Rhovanil® along with the processing of vanillin from clover and lignin can be costly at $50-180/kg. Regardless, natural vanilla or vanillin flavouring will not likely be cheap to source.

Another option is one I did not expect to find, is the possibility of genetically modified (GM) vanilla. Chemical & Engineering News reports that Evolva has found a sugar group known as ‘vanillin glucoside’ through the process of “feeding glucose to a genetically modified microbe”. This form of vanillin is still being researched. It is also uncertain how it will be regulated, labelled, and accepted by consumers. That being said, it’s still an option to meet vanilla flavour demand.

Do Consumers Care?

This leads one to wonder, with demand outpacing the supply of natural vanilla, do consumers care about sources for vanilla/vanillin flavour? If it’s not a big deal (it’s not for me), where will the future of vanilla flavour come from? And if we really do care, then how’ll this impact our future acceptance of non-natural vanilla products? Maybe in the case that natural vanilla is more important and we cannot meet the demand with supply, what new flavour will the food industry replace vanilla with?

If you would like to learn more about vanilla check out:

- “Vanilla –Its Botany, History, Cultivation and Economic Import” by Donovan S. Correll

- Time magazines June 13, 2018 article “Vanilla is Nearly as Expensive as Silver. That Spells Trouble for Madagascar”

- “Why vanilla is so expensive” from Business Insider, September 27, 2018