By Elisabeta Lika

Glyphosate, the active ingredient in many herbicides, has been at the center of numerous debates and discussions in Canada and globally. Its efficacy in controlling a broad spectrum of weeds has made it a staple in Canadian agriculture, particularly in major crops like canola, soybean, field corn, and wheat. Research examining Saskatchewan crop production found that glyphosate is driving sustainability improvements, as the effective weed control provided by glyphosate allows for the removal of tillage to control weeds. However, its widespread use has also attracted attention and discussion from various stakeholders, including governments, environmental organizations, and the industry.

Health Canada, through the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA), undertakes rigorous science-based assessment of glyphosate. In 2017, after an exhaustive re-examination, the PMRA concluded that when used as directed, glyphosate does not present unacceptable risks to human health or the environment. This decision took into account potential human exposures from sources like food, drinking water, and occupational activities. The findings emphasized that glyphosate is not genotoxic and is unlikely to be a human carcinogen. Furthermore, the risks associated with its use, both occupational and residential, are not of concern as long as the updated instructions are adhered to. In 2019, Health Canada undertook a second review of glyphosate use, going even further by stating: “No pesticide regulatory authority in the world currently considers glyphosate to be a cancer risk to humans at the levels at which humans are currently exposed.”

Conversely, there are numerous petitions from environmental organization requesting federal authorities to ban glyphosate, voicing concerns about its potential environmental footprint. These organizations lack robust evidence, rather relying on speculative science, highlighting the possibility of glyphosate entering soil and surface water and the persistence of its breakdown product, aminomethyl phosphonic acid (AMPA). However, these speculative concerns have no legitimacy as the PMRA’s assessment examines data on a wide array of environmental factors for all chemical risk assessments, suggesting that neither glyphosate nor AMPA are likely to leach into groundwater, and neither is expected to linger in the environment for extended periods. The time it takes for glyphosate to degrade can be as short as 3 days, with the typical period being 7 weeks.

The agriculture industry underscores the herbicide’s pivotal role in Canada. Its broad application window, coupled with its effectiveness, makes it an invaluable tool for farmers. Moreover, glyphosate’s significance is accentuated when considering glyphosate-tolerant crops, which have become integral to Canadian agricultural practices.

Internationally, the debate around glyphosate has seen similar divides. While the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified it as probably carcinogenic to humans in 2015, this was a hazard classification, not accounting for actual human exposure levels. In contrast, other regulatory bodies, including the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority, have deemed glyphosate non-carcinogenic. Regulatory agencies around the world that assess the risk of glyphosate use have soundly rejected IARC’s assessment, concluding that it is deeply flawed and not robust evidence of risk.

Internationally, the debate around glyphosate has seen similar divides. While the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified it as probably carcinogenic to humans in 2015, this was a hazard classification, not accounting for actual human exposure levels. In contrast, other regulatory bodies, including the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority, have deemed glyphosate non-carcinogenic. Regulatory agencies around the world that assess the risk of glyphosate use have soundly rejected IARC’s assessment, concluding that it is deeply flawed and not robust evidence of risk.

The recent decision by the European Commission to propose a 10-year extension for the use of glyphosate further supports the scientific evidence. The European Commission’s proposal, based on a comprehensive assessment, suggests that when used responsibly, glyphosate’s benefits in agriculture might outweigh potential risks. There has been a vocal social media campaign by environmental organizations opposed to chemical use in agriculture, but consistent with previous campaigns, these groups are unable to offer any robust evidence in support of their positions.

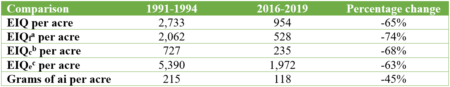

Our recent research paper, submitted for publication, delves into assessing the environmental impacts of in-crop herbicide use, including the use of glyphosate. Many environmental organizations want to restrict or ban the use of agricultural chemicals, including glyphosate. Our results indicate that if this were done farmers would be compelled to use chemicals with considerably higher environmental impacts. Restricting modern herbicides could inadvertently lead farmers to revert to older, more toxic chemicals to control weed populations. This shift could be counterproductive, resulting in heightened environmental and biodiversity impacts. Current agricultural applications and practices have reduced impacts on the environment and biodiversity, so environmental groups are acting in a self-defeating way, as their calls and petitions would result in greater impacts and harm, not less.

Table 1: Environmental impact comparison of top five herbicides: 1991-94 and 2016-19

In conclusion, while it is essential to address genuine concerns about glyphosate use, it is equally crucial to recognize its benefits, especially in the context of Canadian agriculture. As research progresses and more data emerges, the narrative around glyphosate will continue to evolve, but it is imperative to base decisions on robust scientific evidence and comprehensive assessments.

The restrictions would also lead to more mechanical weed control and tillage. Both of which mean exposed soul, soil structure damage and increased erosion. These judges should be dismissing these lawsuits due to the complete lack of evidence or at least passing out directed verdicts against the completely fraudulent plaintiffs. Are they spineless or corrupt?