Calls for transforming food systems have grown over the past several years. International governance organizations, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), have issued many of these calls. Other calls have come from activist organizations, too numerous to list. A common theme from both the FAO and activists is that the current system is ‘broken’ and requires a complete rethink and overhaul. Examples offered on how food systems are ‘broken’ include agriculture’s reliance on synthetic pesticides and fertilizer crop inputs, plant breeders’ rights that facilitate the development of new crop varieties, and the liberalization of international trade rules. The problem with this approach of pointing fingers is that it ignores the accomplishments made over recent decades in food production and supply chains. Yes, food systems are not perfect, there is room for improvement, but to call them ‘broken’ is intentionally misleading.

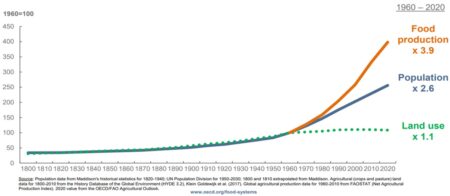

Common themes advocated by activist organizations include a return to ancestral crop varieties, produced through agroecological (organic) production practices that reject the use of yield-boosting synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. When it comes to sustainably increasing crop yields, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development confirms that since 1960, global crop production has increased by 390%, with land use increasing by just 10%, due to farm adoption of improved crop genetics, and the integration of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Before 1960, food production was predominantly done in line with current agroecology/organic requirements, that is, without improved crop genetics or synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. At this time, the only way food production could be increased through agroecology systems was to bring more land into crop production.

Source: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2021.

Activist organizations openly reject over 60 years of robust yield increase evidence, instead advocating myths such as those expressed by the German Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, which states that agroecology “…promises a way out of the vulnerability imposed by monocultures and the dependency on external inputs such as chemical fertilizers, hybrid seeds and pesticides.” Regrettably, activist organizations such as this are communicating false information in countries where food systems require improvement.

Facilitating the food system with trade

Let’s assume there is enough food produced in the world, but it needs to be traded and shipped to meet global demands. The implementation of free trade agreements, starting with the 1995 establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO), is one of the fundamental improvements that has facilitated food system transformation. Before the WTO came into force, barriers were commonly applied in the trade of agricultural products, as well as subsidies that resulted in inefficient production practices. Harmonizing trade rules facilitated the removal of harmful subsidies and improved commodity trade, allowing for freer trade in food products, which in turn contributed to transforming the food production and trade system.

Supply chains have greatly increased the efficiency of commodity movement. Over time, efficiencies have been gained in the movement of food products, such that large warehouses to store products are of less importance. Currently, shipments are managed so that a new shipment arrives just prior to the previous one being depleted. This lowers the space needed to store inventory, as well as the cost of stockpiling inventory. It’s a just-in-time model, which reduces food waste. This increased efficiency is also due to the ability to track specific cargo containers in real-time, as global tracking systems have been established.

Plant varieties and breeders’ rights

Food systems have been transformed when countries have adopted plant breeders’ rights (PBRs). Over time, more countries have domestically ratified the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), which provides public and private plant breeders with the opportunity to protect their varieties. There is robust innovation literature confirming that PBRs increase the incentive to invest greater fiscal resources into the development of new, higher yielding crop varieties. The absence of PBRs creates a situation where minimal investments are made into new variety development by public sector breeders and private sector breeder investments to develop new varieties are minimal, at best. By investing and obtaining PBRs for their plant varieties, these experts can continue to invest in their research and work to solve regional issues. Without PBRs, it may be hard for research to continue in these niche sectors if there wasn’t legal and financial support offered. As changing climates have increased effects on crop production the adoption of PBRs that incentivize the development of new varieties with greater climate resilience, will be even more important.

From the 20th to the 21st Century, there has been a transformation.

Supply chains of the latter 20th century were subject to disruptions due to trade barriers, poor shipment logistics and the lack of investment incentives. However, the 21st century has provided all three of these crucial attributes, resulting in substantial food system transformation. Regrettably, when organizations refer to food system transformations, they often mean a return to early-20th-century models and lower crop yields. Calls for transformation from these organizations are simply called to reject modern innovations that have increased yields by 390% since 1960.

Further support confirming that food system transformation has been achieved and needs to focus on evidence-based approaches comes from the top business and labour committees that serve to inform the G-20 economies. The B-20 and L-20 released a joint statement in August 2024 highlighting key policy recommendations:

- Strengthening rules-based trade to ensure that inefficiencies of protection are minimized.

- Accelerating investments in innovations that have proven yield-boosting capabilities.

- Promoting digital transformations.

Food systems have been greatly transformed in recent decades and there is abundant robust evidence to confirm this. Calls for returns to food systems that reject modern innovations are simply called to politically perpetuate malnourishment and starvation. The food insecure deserve far better than political platitudes but rather require food systems that have confirmed improvement.