It is easy to think of sustainability aspects separately, as if improvement in one area is dependent upon another. There is something to be said for the trade-off nature of sustainability; environmental success doesn’t need to be the only policy focus, as noted in the United Nations Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) designed to address social instability. Zero hunger is one such goal that may be most obviously needed outside of our borders, but food security is an increasingly important, increasingly noticeable problem evolving in Canada.

![]()

Canada is globally ranked seventh in overall food security; when those statistics break down, we rank first for food quality and safety but are 25th in affordability, and 29th in food system adaptability. The comparatively low rankings make some sense given that social sustainability is, by definition, equity in distribution including with food. Unfortunately, the rate of insecurity in Canada, regardless of severity or region in Canada, is rising and food equity still faces domestic barriers in social policy, nutritive quality, and support accessibility. The food security aspect of sustainability is often overlooked so, here, we’re going to look at how it contributes to social sustainability and how far away we are from improved hunger rates.

Western Nutrition

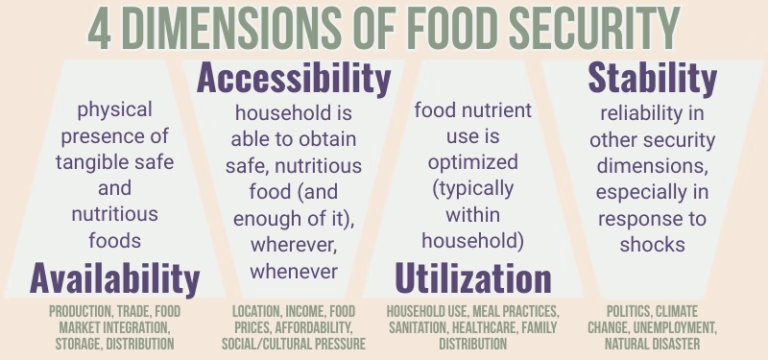

Since 2000, Canadian food production has increased by over 56%, in line with SDG “deadlines,” and thanks in no small part to agricultural innovations. If Canada were to increase food production an additional 28% and our food exports by just over 10% within the decade, global food insecurity could be reduced by over a third. Technically, there is enough food moving around globally that we could solve availability problems but global issues like social/gender equity and efficient resource use (waste reduction) get in the way. Similarly, food security is a multi-dimensional concept (Figure 1) therefore, the focus of Canadian food security efforts should no longer be in the productive space (despite how vital for economic sustainability and its trade-off with the environment) since we are already successful there. The Canadian mindset should instead shift toward one of health and nutritive support.

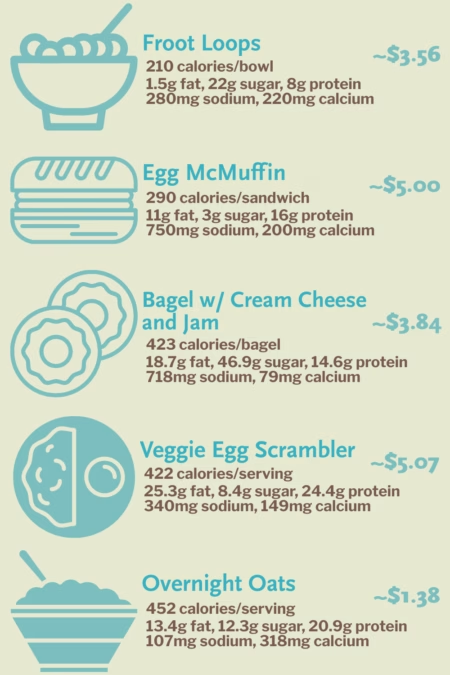

The Canadian Food Guide is designed to encourage food mindfulness of nutrient-dense foods and limit sodium, fat, and sugar intakes, rather than dictating what to eat. Although Health Canada acknowledges some solutions to the healthy eating challenge, policy that exclusively focuses on nutrition is often inconsiderate of increasing food prices, dietary preferences, and institutional or accessibility barriers. Further, there exists a complicated insecurity cycle fed by nutrition. A “healthy diet” is 60% more expensive than one that only considers essential vitamin and mineral requirements and therefore may not be affordable for any given household (Figure 2). Cheaper substitutes with perhaps lower nutritional value are then pursued, although, according to the security dimensions, this does not guarantee food security due to availability alone. A consistently low-quality diet can exacerbate health risks and vulnerabilities such as malnourishment, an affliction for less than 3% of Canadians. Food insecure individuals unable to purchase meals for their families are subsequently and rightfully less concerned with seeking medical attention than finding lunch for tomorrow, further increasing both the rates of insecurity and the necessity of immediate relief like food banks. Consequently, long term structural support required for meaningful food security improvement is either no longer prioritised or no longer feasible.

The Great North

Canada’s territories and First Nations reserves are often excluded from federal food security reports and definitions, hiding the physical and cultural struggles in the north that cannot be equally applied to southern provinces. Reports from York University in Toronto suggest that Indigenous communities – who dominate territories populations – are twice as food insecure as the Canadian average, and the difference on reserves is even higher. The remoteness compounds these problems, as evidenced in Nunavut, which is approximately 20% more insecure than other Inuit populations.

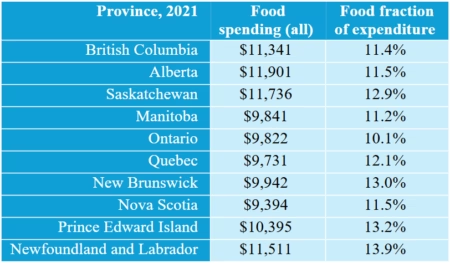

Physical food availability and accessibility limitations challenge diverse, fresh, whole food, and nutrient-dense diet are realities in the north. Fewer grocery stores, trips to those stores, and increased climate change impacts to traditional (i.e. hunting, fishing, harvesting) food availability create a freezer-friendly, low perishability north. Northern accessibility also limits healthcare services which, as discussed, can limit food security improvement if nutrition risks an individual’s health. Remoteness can decrease the number of employment opportunities, reducing the average income in the north and creating a purchase-for-necessity culture. 25%, 39%, and 81% of total sales in Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut, respectively, is food, notably higher than what the provinces on average are expected to spend (Table 1).

Nutrition North Canada (NNC) contains a food subsidy program that incentivizes remote retailers to sell fresh, minimally processed food items, since northern food prices are inflated as a reflection of high transport costs from distance and infrastructure challenges. Businesses are paid and charge less for a select list of goods (the Revised Northern Food Basket), provided shoppers know how much the government contributed on shelf labels and receipts. While food price stress is partially alleviated, very low-income households can afford at most 13% of the Revised Northern Food Basket and critiques of the NNC subsidy suggest that ordering efficiency, confusion over reporting requirements, cultural foods exclusion, and ignoring dietary preferences limit the cost savings potential of the program in the north.

Food Relief Going South

In general, the Canadian rate of food insecurity has followed a similar trend to food prices, a player in the cost-of-living crisis that has globally exploded post-pandemic and increased food bank reliance across the country. Between 2021 and 2022, the number of food bank visits in Canada increased by 15%; that figure would be dwarfed in the 2022/2023 value, reporting a 32% increase in visits, before the growth rate would slow to 6% by early 2024. As a result, there are now four times as many charitable food distribution centres as retail food options, which provides some unfortunate clarity into Canada’s food security policy.

Food distribution centres and recovery program follow charity models meaning they rely on quality donations to remain operable. This also makes donating one of the most visible ways to address food relief, although there is no evidence that they have made any impact on food security rates. When government uses food bank donations as their primary response, it passes problem-solving on to communities with access to fewer resources and doesn’t address the underlying reasons for insecurity.

Concluding Remarks

Requiring food relief in an increasingly expensive Canada is neither an embarrassment nor an exploitation of resources. In the absence of food price stability, individuals will turn to food banks as a last and incomplete resort. But 78% of food insecure families live above the poverty line, indicating a clear socioeconomic problem that has be exacerbated by global events, including recent American tariff threats. The creation of policies that match social assistance with the rate of inflation or improving access to financial and social services could provide structural relief to food security issues and reduce reliance on community food banks. Addressing northern rates of unemployment and the declining value of income may partially compensate high food costs, although these solutions require action. Social sustainability is a vital player in Canadian development and by having overlooked it for environmental and economic priorities, communities are beginning to realise the necessity of long-term system stability.

Curious how your riding measures up to Canadian food security rates, or how to start the food security discussion with your local Member of Parliament?