Review Evidence from Noack et al. (2024)

Here, on SAIFood, our opinions on genetic modification (GM) have been apparent: we know that they are beneficial tools which, when employed in agriculture, are being used to meet calls for increased food and food security, including limiting the environmental impacts from agriculture in general. While trade-offs exist with the widespread use of any technology, the public fear of GM appears to be misplaced, seemingly latching onto environmental and health risks as though they are side effects of use. However, the role of GM in improving or worsening the current global environmental crisis is much deeper than simply banning GM or adding regulations. As described in a recent article by Noack et al. (2024), Environmental Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops, the discussion of GM in the food/feed system, domestically and internationally, is more nuanced than assigning blame.

Before any further discussion, it is important to note that commercial GM traits are typically confined to herbicide tolerant (HT) and bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). Exceptions do exist (see: the Flavr Savr tomato, which was inspected and determined safe for Americans and Canadians, but failed to meet consumer acceptance and market success) however, these are the primary traits that dominate GM soybean, corn, canola, and cotton species. Part of the reason for such a limited availability is because of the expense and rigidity in GM regulations which, in the process of guaranteeing potential negative impacts are negligible, discourages food novelty and increases seed prices. This blog isn’t about commercialization, it is about the impacts of GM use, but this introduction hopefully emphasizes GM approval and use in Canadian food systems is not casually approached.

What We Know About GM

The primary purpose of the article is to bring together global conclusions about GM. While there may be dissension depending on the nation, many researchers have come to the same conclusions not only about the negligible health impacts of consuming GM products but also about how GM adoption impacts the environment. “Negligible health impacts” refers to the direct consumption of GM as health consequences as a result of production (i.e. other inputs) are still very much present. Determining how many of those impacts are a direct result of GM is unclear because chemical use/type, personal protective equipment, and overall GM presence differ across farms and countries. In general, the widespread adoption of GM has led to decreased reliance on chemicals; in theory, HT reduces the amount of herbicide used in the field while Bt reduces the necessity for insecticides. Unfortunately, this mechanism is theoretical as, in reality, GM crops have increased chemical reliance, and water contamination has become a common finding in GM research.

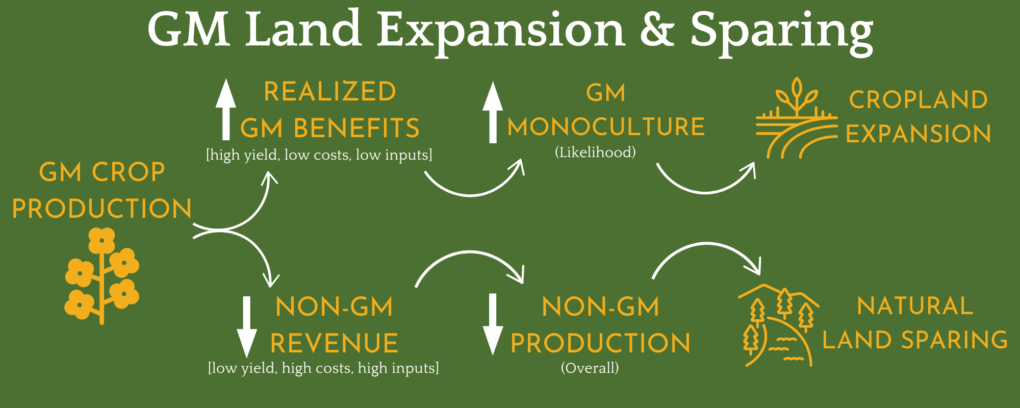

This partially explains why biodiversity conclusions are so varied. The worry that GM varieties are breeding with wild plant species is present in research, however, it is argued that such comes from trials as opposed to field-realistic conditions. But beyond direct biodiversity results, Noack et al. (2024) discuss the indirect biodiversity loss from widespread GM adoption. The high-yield potential of GM crops (and associated economic performance) has encouraged agricultural simplification and cropland expansion, decreasing productive diversity (or crop rotations) and natural biodiversity, respectively. Of the two consequences, expansion seems to be more subjective (Figure 1) depending on market outcomes and the subsequent response of non-adopters.

Similar management complications are found with the uptick of zero-till adoption since GM commercialization in the mid-1990s. Zero-till has many benefits for soil structures and successive yields, albeit inconsistently. Setting aside the greenhouse gas emissions implications of running less equipment across the field (which can be a controversial benefit of use), GM adoption appears to have helped link farmers with conservation practices. The plurality of “practice” is where conclusions are muddled, as it is suggested by Noack et al. (2024) that zero-till benefits, while promoted by GM crop adoption, are linked to the combination of (conservative) management practices opposed to a single practice.

What's Left to Research?

Determining the true environmental impacts of GM crops requires a holistic approach, recognizing the direct and indirect consequences of management. However, the underlying theme of Noack et al. (2024) is that we don’t know enough or, rather, that what we do know about GM can only ever be narrowly applied. The longevity question is of particular concern: how can we assess GM performance if we don’t know how biodiversity, chemical resistance, or agricultural expansion will perform in fifteen years? The farm-specific considerations of adoption, both logistically and economically, are enough to create uncertainty in any of these parameters. Further complicating how little we understand of the impacts of GM is the (environmental, economic) spillover onto non-adopters.

The industry itself could also do with reformation, as Noack et al. (2024) sufficiently point out that field trials used to inform safety/performance are often incompatible with real-world farms or the characteristic diversity therein. This is a common critique of herbicide toxicity research, which often inadequately assesses risks such that hazards, instead, are over- or underestimated. Similarly, it is difficult to scale up field trials, resulting in ten-acre experiments informing 100-acre consequences. Without understanding the indirect consequences, GM cannot be adequately evaluated for commercial fields, and the reputation of GM cannot improve.

Interested in reading the full article this blog is based on? Please follow this link:

Environmental Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops (Noack et al. 2024)